Before the 1953–1959 Cuban revolution and during Fidel Castro’s lengthy dictatorship, Cuba was a wellspring of European-influenced Modernism and a launchpad for Modernist designers. Some of the conception and manufacture was a remnant of the Batista era, a period when Cuba was a virtual playground for United States and European businesses, both legitimate and criminal. Many consumables, notably cigars and rum, were produced for export prior to the strict and lengthy prohibitions imposed on the country. Meanwhile, Modern wares—particularly furniture—drew influence from Western forms and styles until the Cuban government nationalized their manufacture.

Today, there’s a renewed scholarly and curatorial interest in Latin American furniture, product and graphic design. MoMA is currently exhibiting Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1920–1980. The recently published Diagramming Modernity: Books and Graphic Design in Latin America, 1920–1940 covers a largely unknown swath of publication and typographic history. And the forthcoming A Modernist Regime: Cuban Mid-Century Design—the first comprehensive museum exhibition dedicated to Cuba’s Modern design movement—will feature objects never exhibited outside of the country. The exhibition opens at Cranbrook Art Museum on June 15, and will run through Sept. 22; the excellent eponymous book is available now.

A Modernist Regime was co-curated by Cranbrook Art Museum Chief Curator Laura Mott, design historian and curator Andrew Satake Blauvelt, and curatorial fellow Andrew Ruys de Perez. The show originated with Abel González Fernández, an independent curator who was based in Cuba when the project began but is now Associate Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

I recently conducted the following interview with Blauvelt, who also wrote essays in the book on the highly regarded OSPAAAL posters and the export of Cuban graphic design as means to globalize Castro’s ideology.

In your revelatory book I am particularly struck by the photo of Fidel Castro lounging in a Modern-furnished room. The photo suggests the “hope” that Modernism symbolized, but also suggests the American and European influences that were so prevalent in pre-Castro Cuba. Can you explain what you mean by A Modernist Regime?

“A Modernist Regime” is a way of identifying the idea of Modernism within the Castro regime that comes to power in 1959. We usually associate Modernism with socialism and capitalism, historically. What struck us about this story is how Modernism transforms in Cuba under different political economies: first, under an autocratic capitalism of the Batista regime, then under a promise of social democratic reforms by the early Castro regime, and then again under a communist dictatorship. All three phases are influenced by the Cold War politics of the U.S. and U.S.S.R., of course, as well as the non-aligned nations that sought autonomy from these superpowers.

Was Cuban design Modern by default, having been imported into the country by the previous regime, or was it symbolic of the new era to come?

Modernism in design was introduced in the 1930s by Clara Porset, and important furniture designer who had studied it in Europe and the U.S. Interestingly, she advocates for a Modernism that could be adapted to the Cuban culture and climate. Although she was from a well-to-do family, she was drawn to the social, egalitarian promise of early European Modernism. These political beliefs led her to be exiled from Cuba for most of her adult life as she fled the Batista regime for Mexico. She briefly returned to Cuba when Castro came to power, hoping to see the transformation of Cuban society and to lead a design school there, but that did not happen and she returned to Mexico after a couple of years.

Midcentury Modernism was definitely a presence in Cuba, especially Havana, which was the tourist center for the country, and given its proximity to the U.S. and the volume of American visitors it would take hold. At one point Knoll furniture company even opened a showroom in Havana. This was definitely an imported Modernism, more capitalist and Western in nature. There were Midcentury residences and hotels built before the revolution, for example.

The book and exhibition cover the designers who were associated with progressive design movements and groups. Was this encouraged as an alternative style compared to the previous regime?

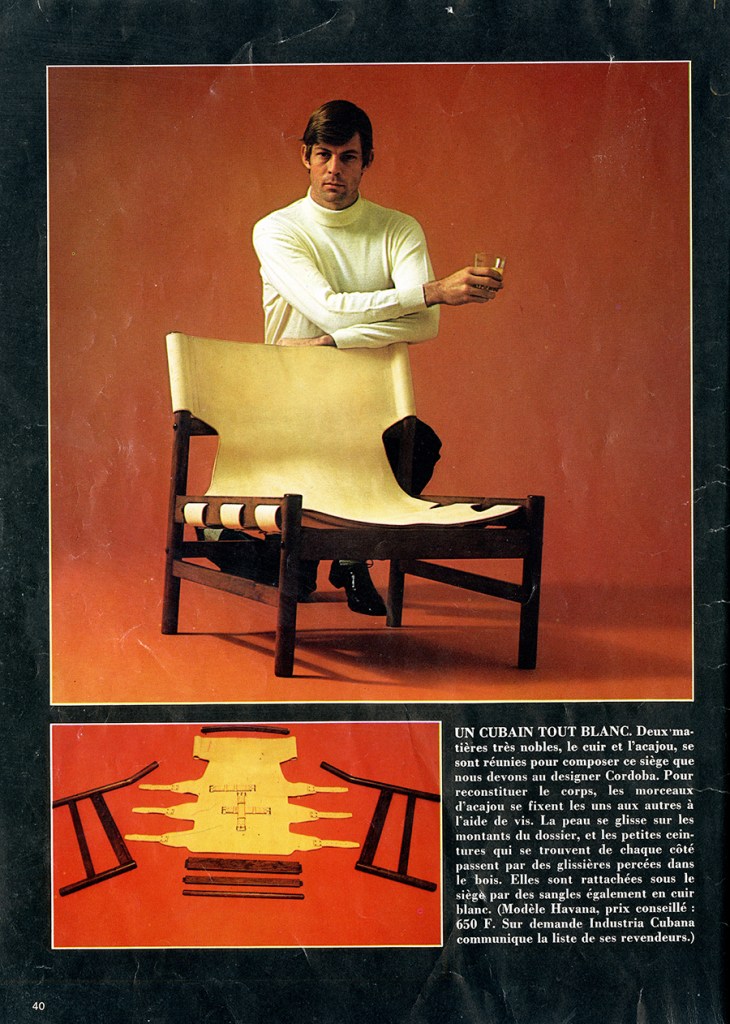

The idea of Modernism shifts after the revolution. In the show, we focus mainly on furniture design. Since there is no private enterprise under the Castro regime, the government becomes responsible for design and thus creates companies or enterprises to deliver those goods. Inevitably, it inherits whatever was in place before 1959. So, design continues on, but it adapts to its new socio-economic-political circumstances. The regime creates a Modern furniture company called Dujo, whose design director is Gonzalo Cordoba, who was a furniture designer before the revolution but chose to stay in Cuba when many others fled.

Dujo furniture was created mainly as an export product and was shown and sold in Europe. It resembles Danish modern furniture but utilized native woods and local materials. I should note, however, that Scandinavian design took much of its inspiration from the tropical environs of the Global South, exotic woods and rattan or corded upholstery, for instance. So, the idea of influence and innovation under Modernism is a complicated story! Dujo furniture was also used in the offices and homes of high-ranking government officials. So, we find it in Castro’s office. Later, the government began focusing on domestic furniture needs and designers responded with explorations in new ways of making such goods in large volumes. It created a new company called EMPROVA and the Light Industry Group to explore such things as panelized and user-assembled furniture, flat-packed goods, and modular designs.

Was Cuban design deliberately attempting to reject Soviet-style communist/socialist “Modern”?

Interestingly, the country did not adopt a national style like social realism in the USSR under Stalin or in China under Mao. Social realism was the rebuke to Modernism and abstraction, in particular. As Cuba fell under the influence of the Soviet Union (it was under an embargo by the U.S. since 1960), it adopted more of its products and thinking. For example, prefabricated architecture emerged in Cuba before the revolution, where it made sense because of the lack of certain materials and manufacturing capabilities on a small island. This exploration continued after Castro came to power but eventually gave way to more expedient solutions imported from the U.S.S.R., like concrete slab construction for housing. It was efficient, I suppose, but ill-suited to the climate and aesthetically non-descript—the exact opposite of the glamour associated with Midcentury Modernism, for instance.

You state in your foreword, “Cuba also presents an interesting subject for design history given the country’s colonial history and multicultural legacy.” How does this manifest in the Midcentury aesthetic in Cuba?

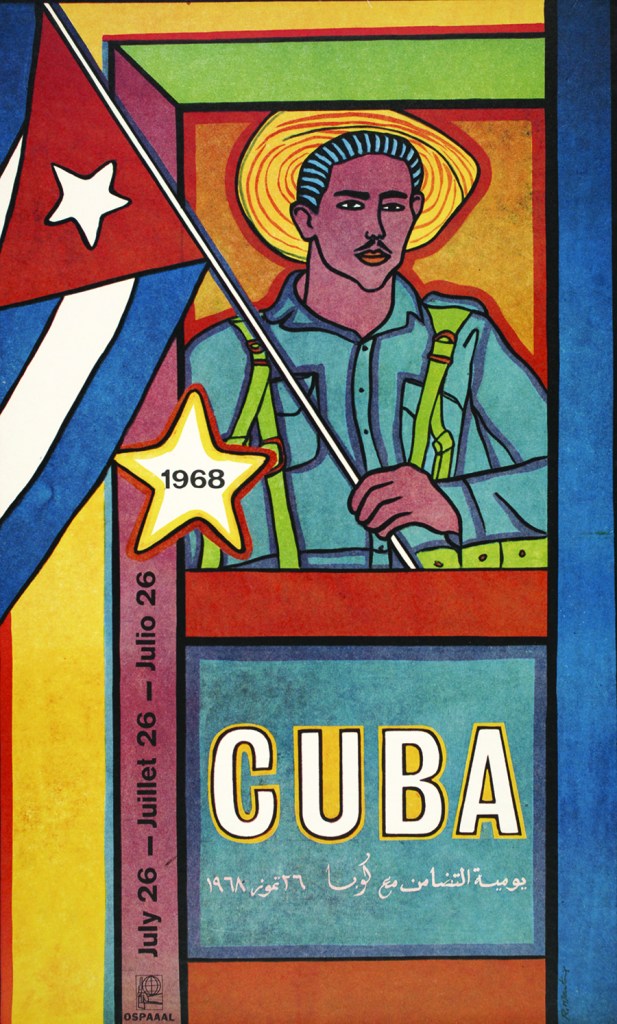

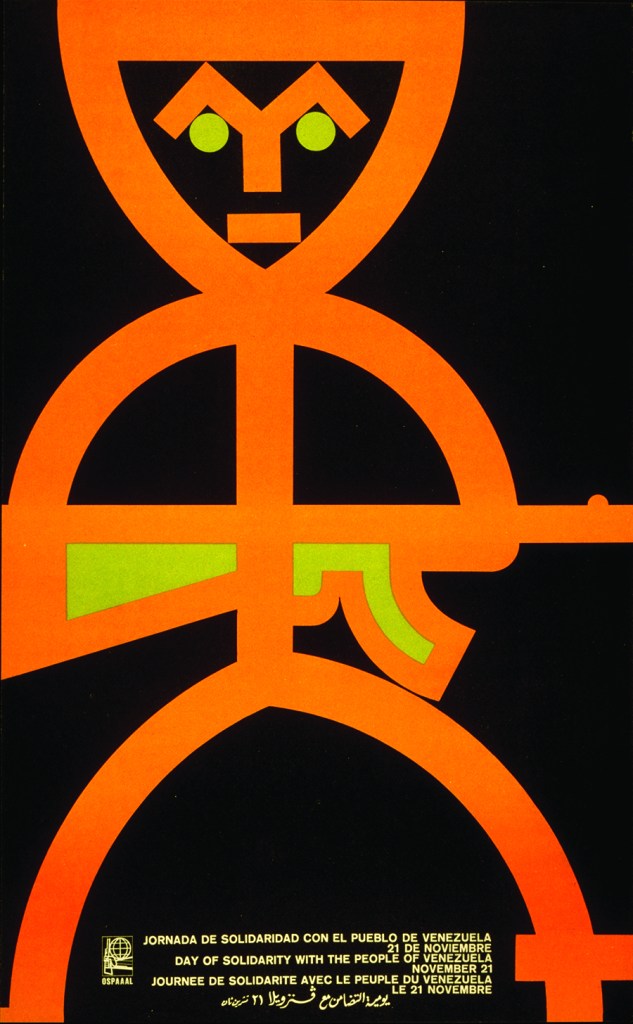

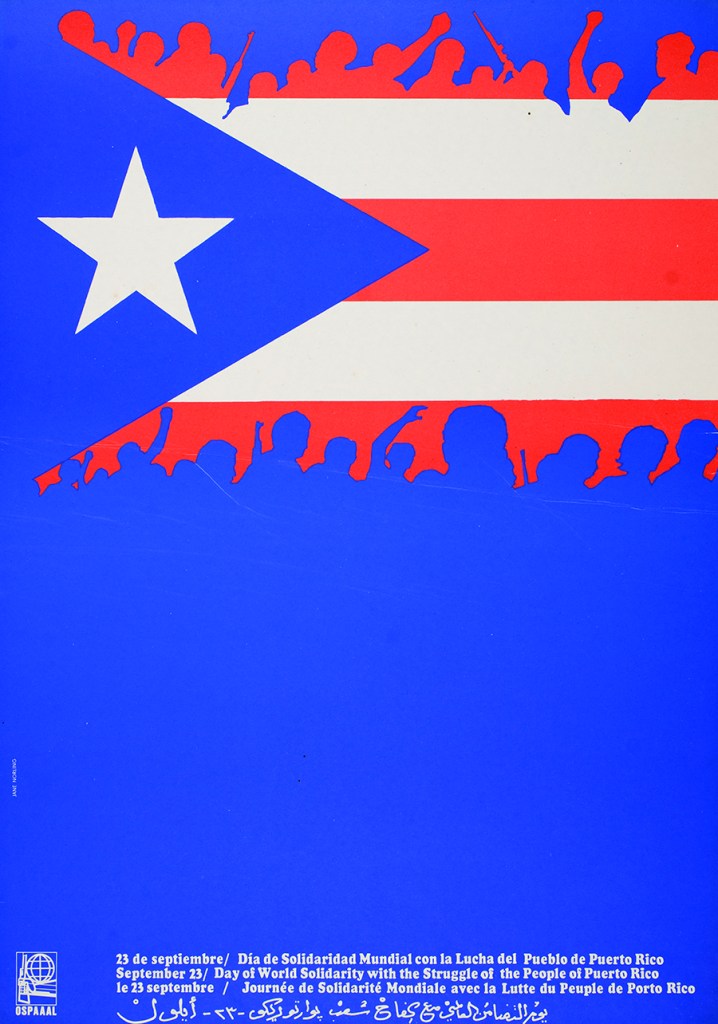

For the furniture, we see especially in the Dujo line, a recourse to Cuba’s indigeneity—even the title of the company is a reference to a duho chair, a ceremonial lounge chair used by the Taino peoples who inhabited the Caribbean before Columbus. Some chairs referenced Taino artifacts and objects. There is a moment of historical reflection in Cuba, on this particular past, that I equate with the need to link to precolonial histories, a way past the dominant colonial legacies of exploitation, slavery and extraction. This I see also in the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL) posters, which were designed for mostly non-Cuban cultures, countries also escaping their colonial histories and legacies. For OSPAAAL, we see the use of the precolonial warrior figure as analogous to the contemporary freedom fighter or revolutionary. OSPAAAL also supports the American Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the U.S., drawing linkage between its own Afro-Cuban legacy of slavery and diaspora.

Another packed quote to unpack: “European modernism was transformed as it was introduced to pre-revolutionary Cuba.” How, in fact, did this transformation manifest? Did the designers ultimately have to conform to a state-sanctioned aesthetic? Or did Castro’s regime give license within the parameters of available resources?

In most ways, Modernism, understood as a European project, was transformed anytime it left its origin. That said, it was transformed when it came to Cuba, as I mentioned above, when it encountered a tropical environment, for instance. Porset was good at explaining that traditional heat-trapping upholstery would not be the best in Cuba, so the use of natural fibers woven with air circulation in mind. Or the use of local woods, called “exotic” in European counties. The OSPAAAL posters are also an intriguing blend of many styles and influences. It is so eclectic in fact it’s hard to call it Modernist by any strict definition—maybe pan-Modernist. Perhaps I would even call it Proto-Postmodernist when one views it collectively. All of this happens within a small historical window of opportunity—when Modernism could be imagined to be a more egalitarian solution to the people’s problems. Ultimately, many of these artists and designers grow disillusioned with the Castro regime and its increasingly authoritarian policies. This culminates today in a state which strictly controls what can be produced by artists, imprisons and forces into exile voices of dissent.

Where did all these artifacts come from? Who or what has been collecting these rare Cuban Modern examples? And is Cranbrook the first North American museum to display them?

We are indebted to two individuals for this project: Marco Castillo, who recognized that this furniture needed to be preserved and has done so. Most of the furniture is from his collection. And, curator Abel Gonzalez Fernandez, who recognized the importance of telling this history. Some designs, particularly in the 1970s, were only ever prototypes, so some of these are being recreated for the show with the assistance of the original designers. The objects have been on view in Cuba in smaller exhibitions but not in a museum in or outside of Cuba. This will be the first time at Cranbrook. The OSPAAAL posters are different and were quite celebrated in their own time, along with other forms of Cuban graphic design, particularly the country’s film and propaganda posters of the 1960s and 1970s.

The exhibition is, as you say, mostly about furniture and architecture, but let’s talk briefly about the posters. Cuban posters have long been on the cutting edge in terms of entertainment, information and propaganda. How do they fit into the book and exhibition’s focus on Midcentury Modernism?

I wanted to include the OSPAAAL posters and some examples of experimental architecture from the same period (1960s and 1970s) because they also deal with Modernism in their own unique ways. In my essay, “Becoming Modern: Importing Modernism, Exporting Revolution,” I wanted to show how graphic design and architecture participated in the same flows—being transformed by Cuban hands and minds but also by the state and its ideology, particularly when it left Cuba and was on an international stage.

Our stereotypical American view of Cuban design focuses on a frozen time period—mid- to late ’50s-era cars, architecture, signage—all nostalgically yet practically/functionally preserved. So, how has this project altered the perception of Cuban revolutionary style?

Interestingly, this furniture is now being preserved, refurbished, but only because it’s being collected. Typically, objects in Cuba are used until they are no longer able to be used—such is living with the scarcity of materials and goods under an embargoed Cuba. The Cuban government has not been interested in preserving this part of its history. The stories exist with the designers, many of whom are no longer alive, unfortunately. I hope we are able to help preserve this history and to enlarge the circle around it. I also hope that we can reflect on Modernism through a different lens. What would the story of Modernism be if it were written from the perspective of the Global South instead? I’d like to hear more stories like that.