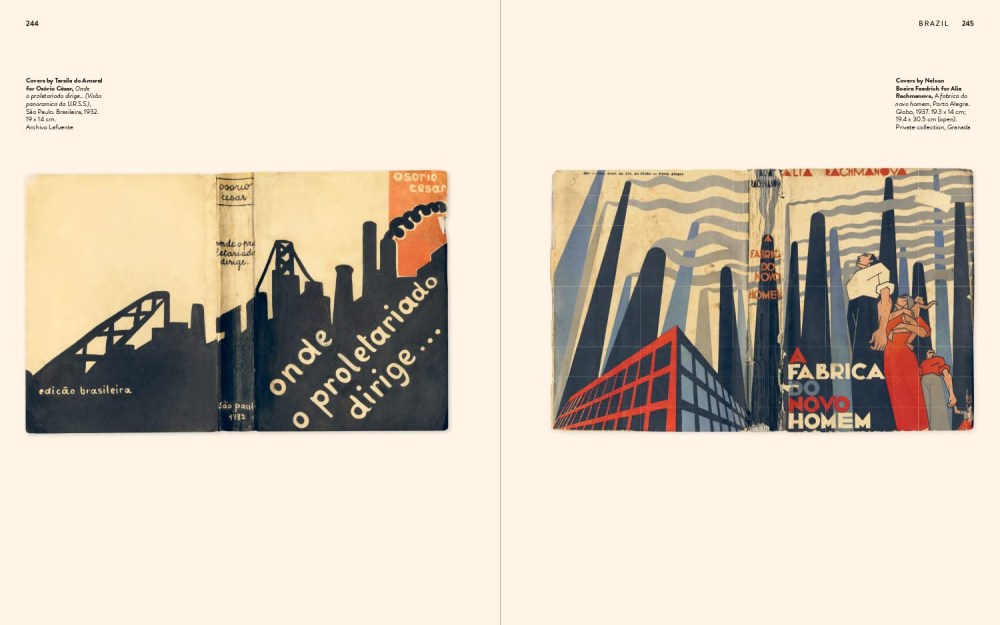

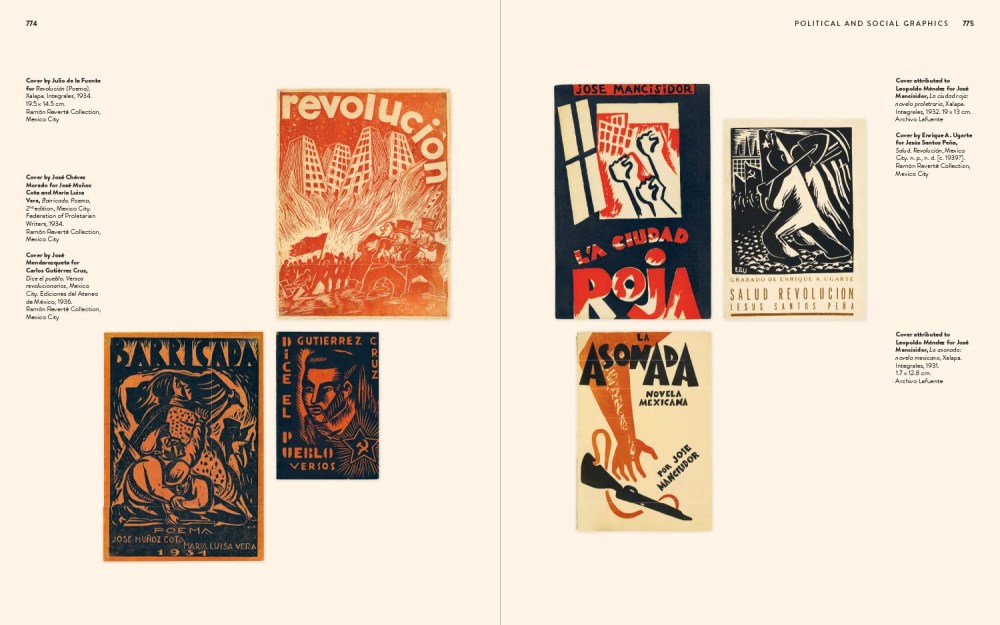

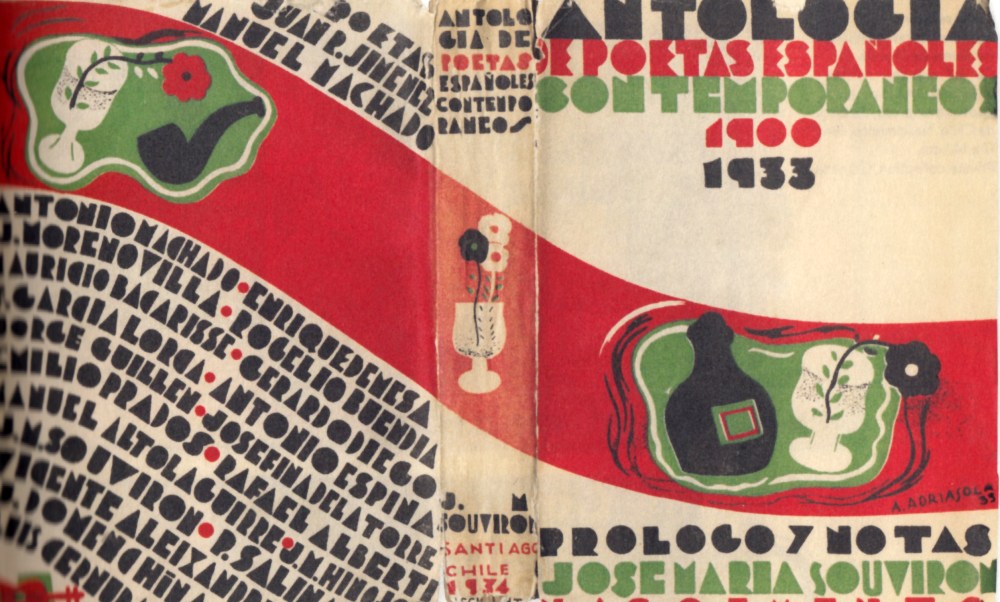

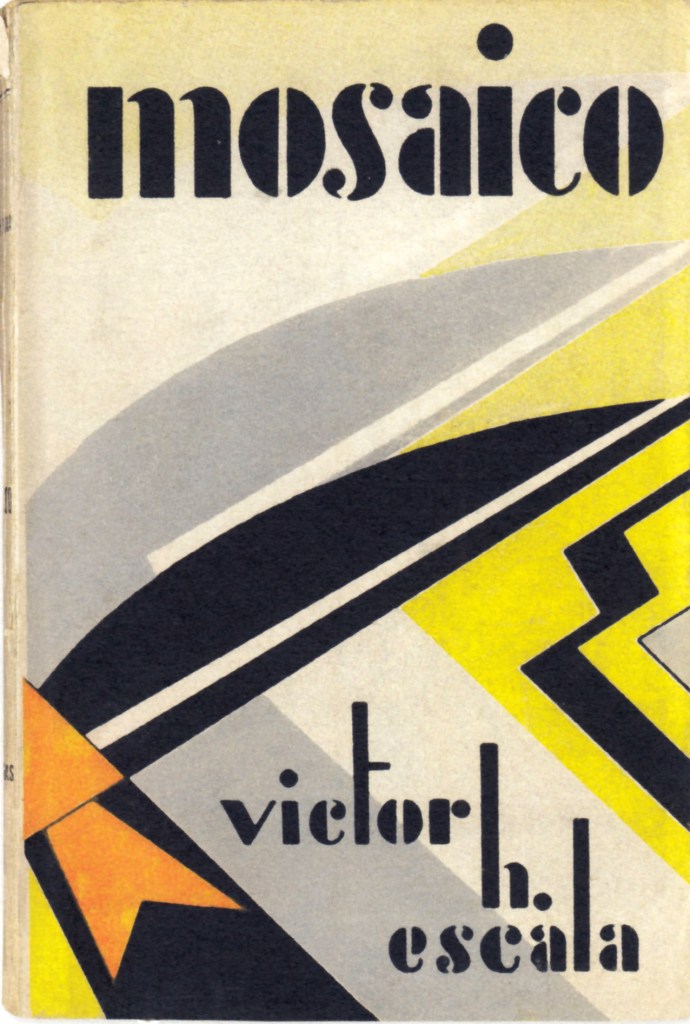

Latin America is known for much antiquity and contemporary art and artisans. However, as the history of graphic design study expands, it is becoming known for its own avant gardes. Many of these owe debts to European modern movements. Many are social, political and cultural manifestations. Some are revolutionary. Modernist visual languages vary from dialect to dialect, nation to nation, but they share common roots. Diagramming Modernity: Books and Graphic Design in Latin America, 1920–1940 (Ediciones La Bahia) by Rodrigo Gutierrez Viñuales and Riccardo Boglione gathers in one thick volume a “transatlantic journey” in alphabetic order—from Argentina to Venezuela—of what the co-authors call “Verbovisualidad: The Visual Representations of Language.” Having collected bits and pieces from here and there of the material shown and discussed, I’m glad there is an English version to explain the origins of form and style, while highlighting some of the key practitioners of these two decades when avant gardes in Europe influenced art and design across the world.

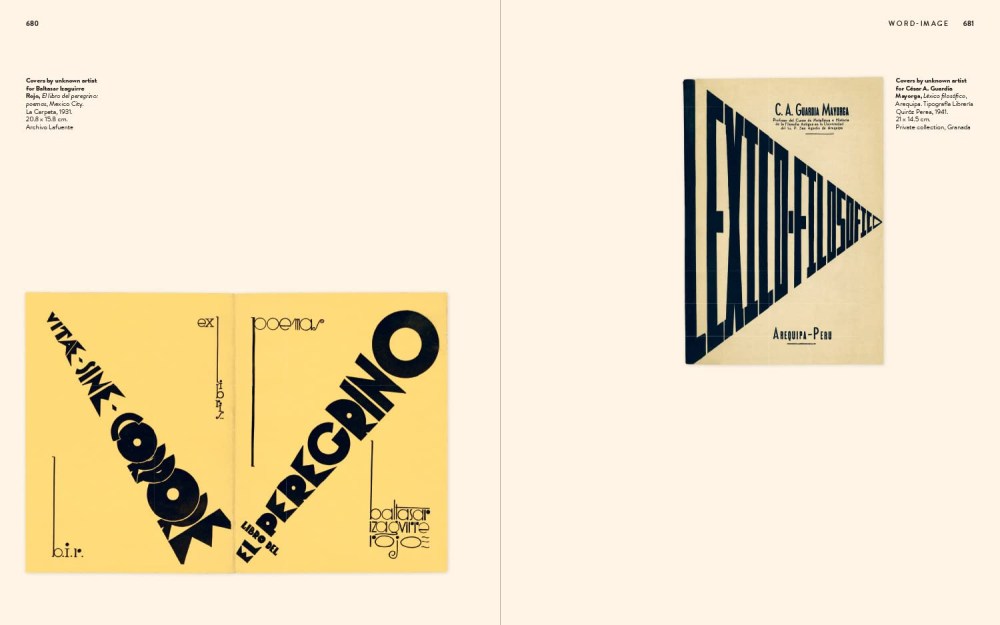

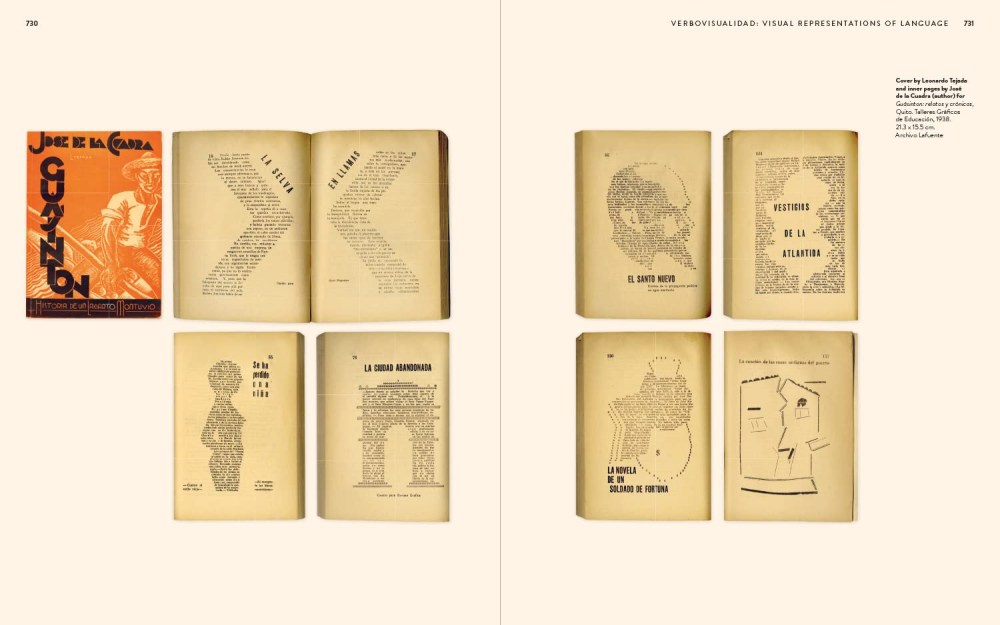

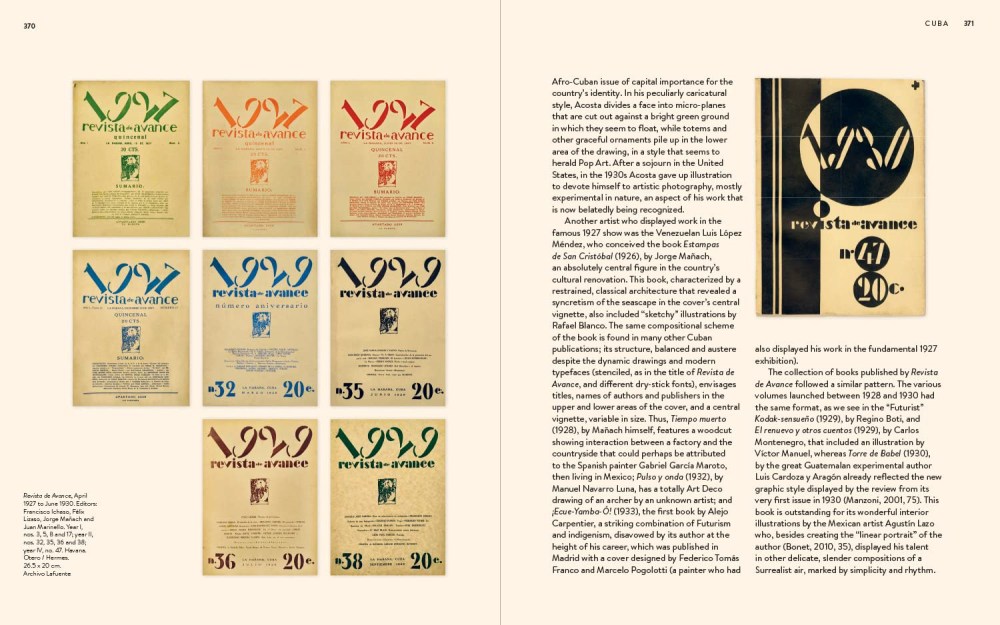

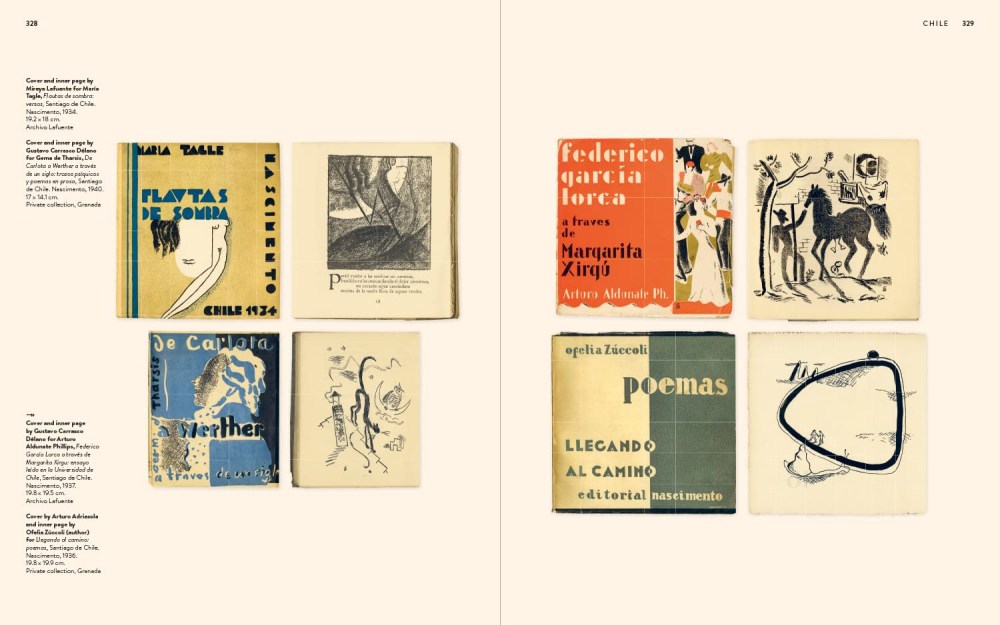

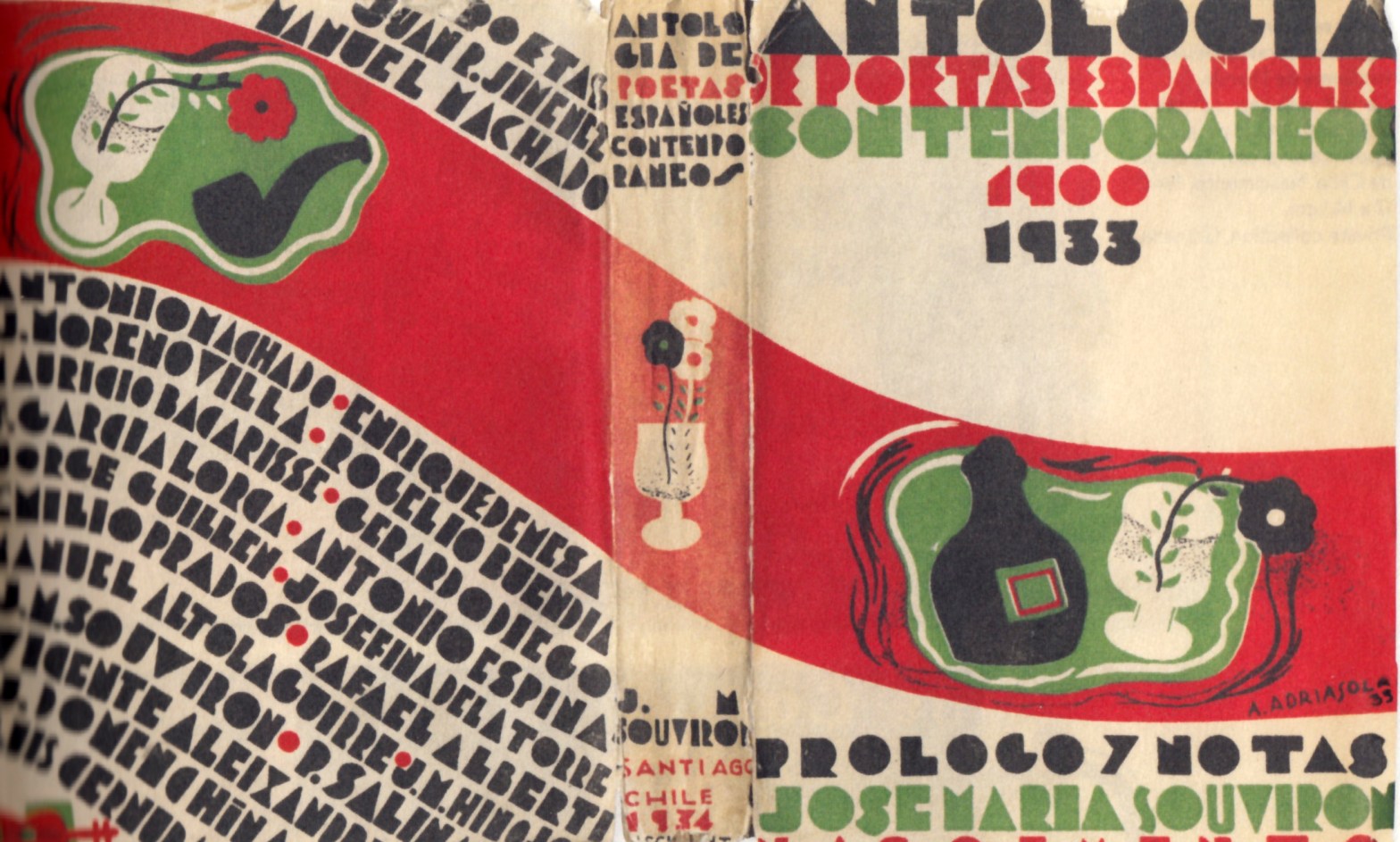

“One of the main purposes of this survey,” write the co-authors, “was to try and transmit the importance of the visual construction of modernity” through a trove of book and magazine covers. “These areas often became spaces for formal experimentation in the case of artists who were more used to working on canvas. … As a result, the artists enjoyed a fair degree of freedom, further encouraged by their incipient interest in using striking designs to catch viewers’ attention in store windows [italics mine].” Sometimes the illustrations, typography and compositions echoed “the same freedom” and even were “continuations of outer designs.”

The title of this book suggests the co-authors’ decision to avoid the term avant garde as focusing on European work that would force the “subordinate” view of Latin American design. Their achieved goal is to show that Europe alone was not the entire inspiration for what was Modern. They point to Mexican Stridentism and muralism and Chilean Runrunism as more homegrown and indigenous. For them “modernity” describes attitudes that were adopted by key artists and associated groups, which when seen together impart a holistic yet individualistic practice. In Diagramming Modernity the idea was not to prioritize nationalities but to describe and analyze “small societies” of progressives who have been forgotten or ignored. The names of these pioneering artists/designers are doubtless unknown to most of us in North America and Europe, but thanks to Gutierrez Viñuales, Boglione and other proactive design historians, they are now revealed for future scholars and collectors to newly explore.