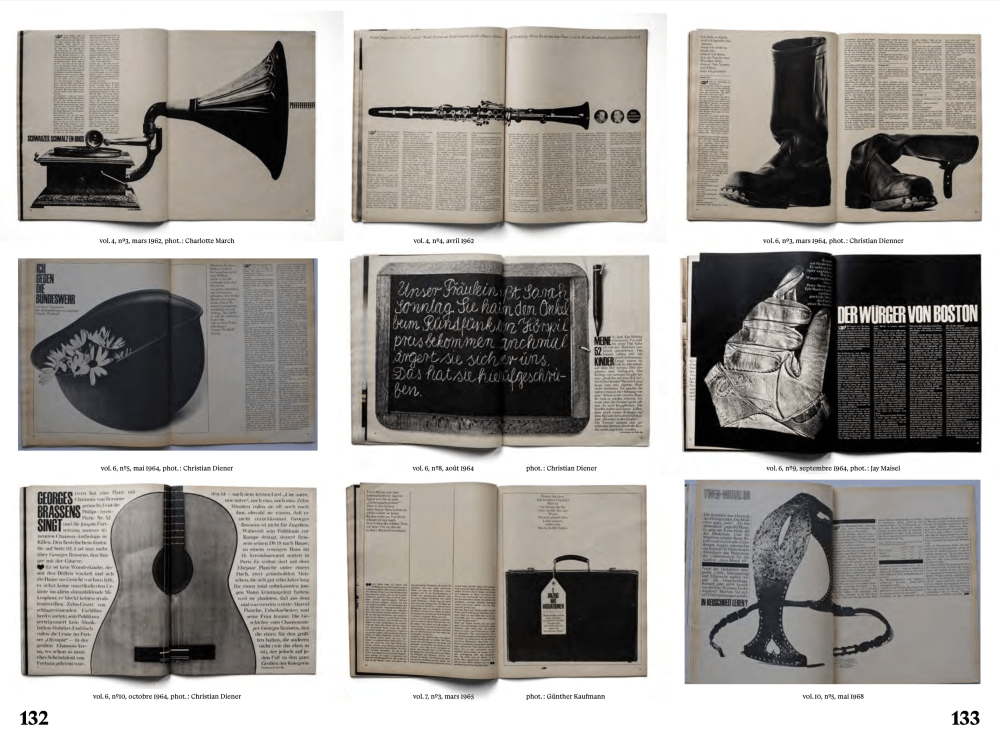

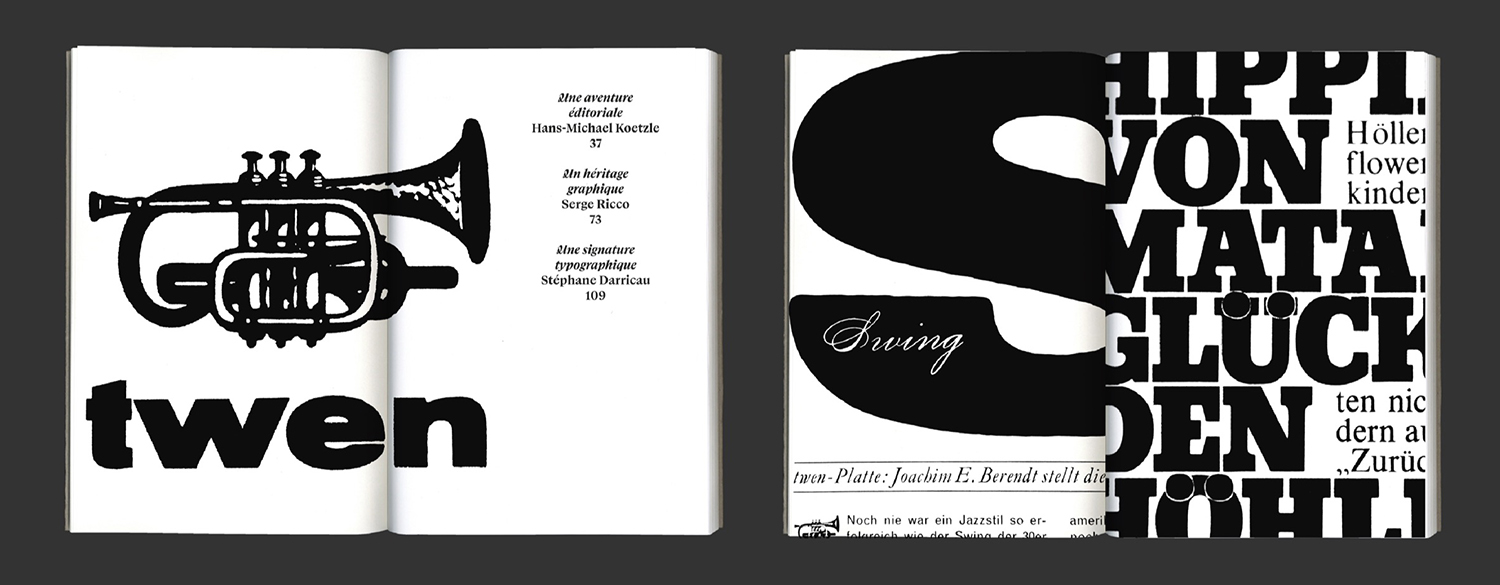

From the 1950s through the 1980s, mammoths of magazine design and art direction walked the earth. Arguably the grandest of them all was twen, art directed from 1959–1971 by Willy Fleckhaus. His orchestration of content—word, type, picture, layout—was nothing less than symphonic. He was the maestro.

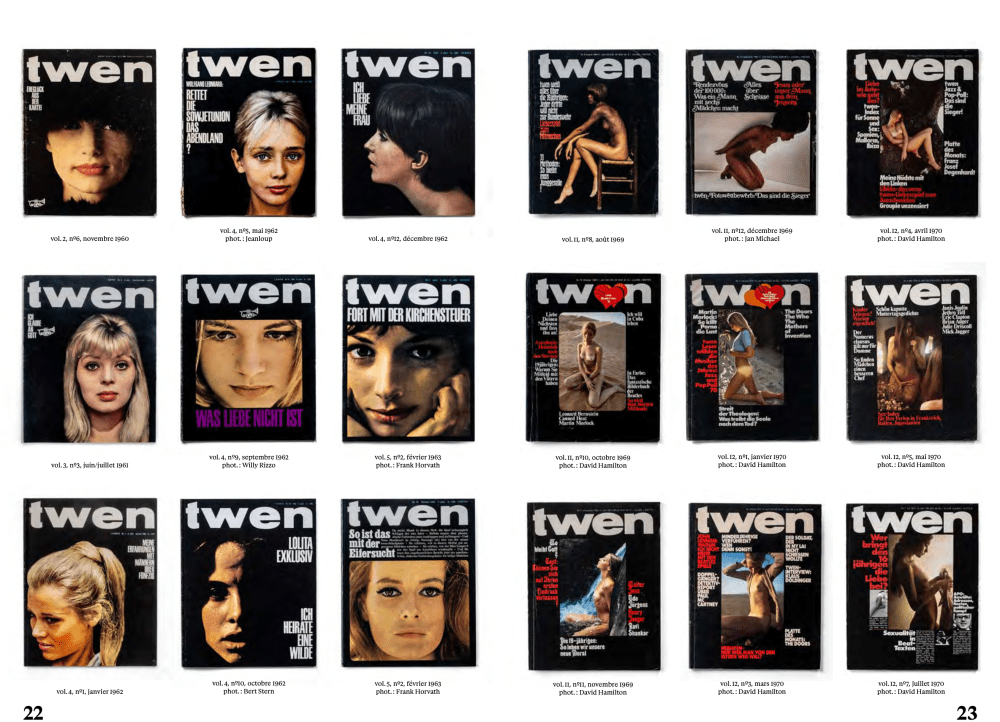

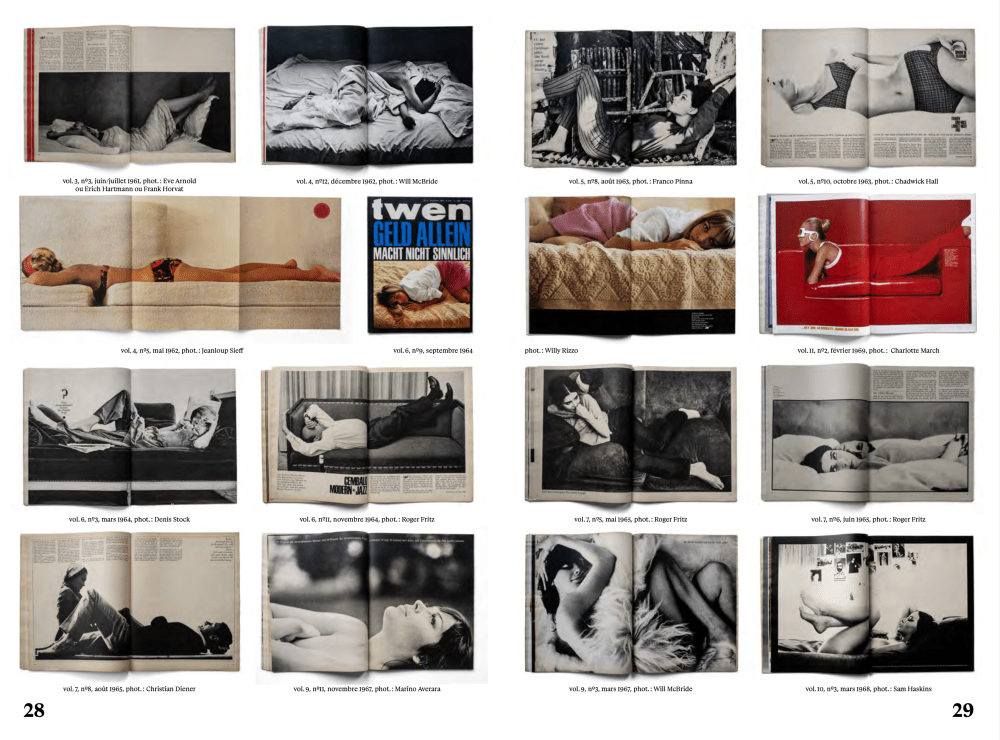

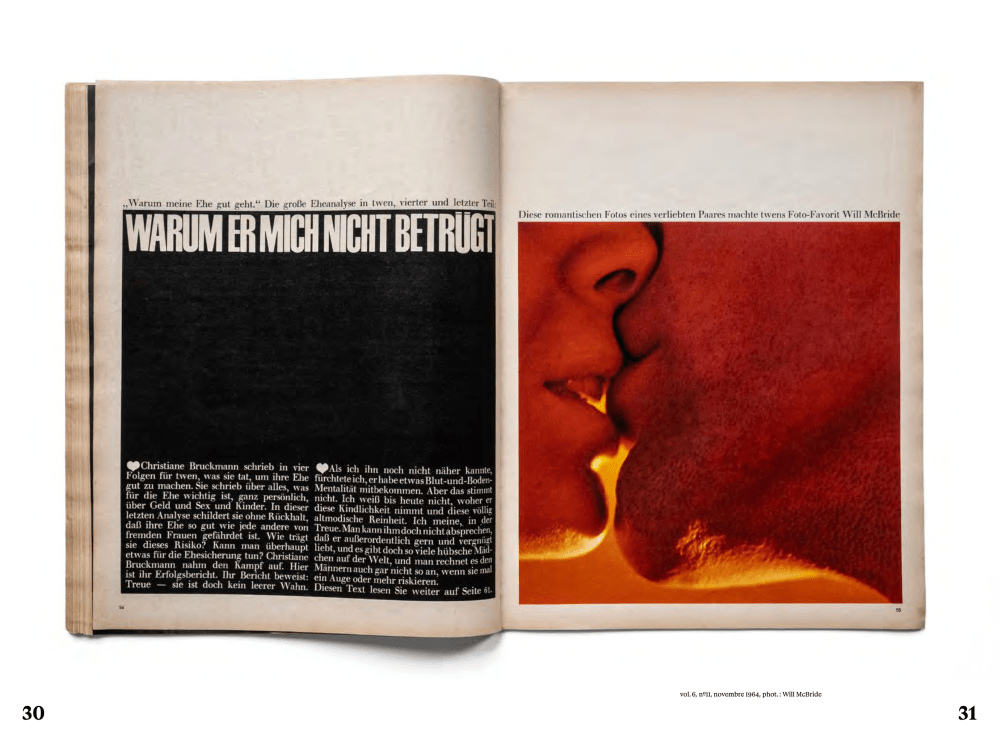

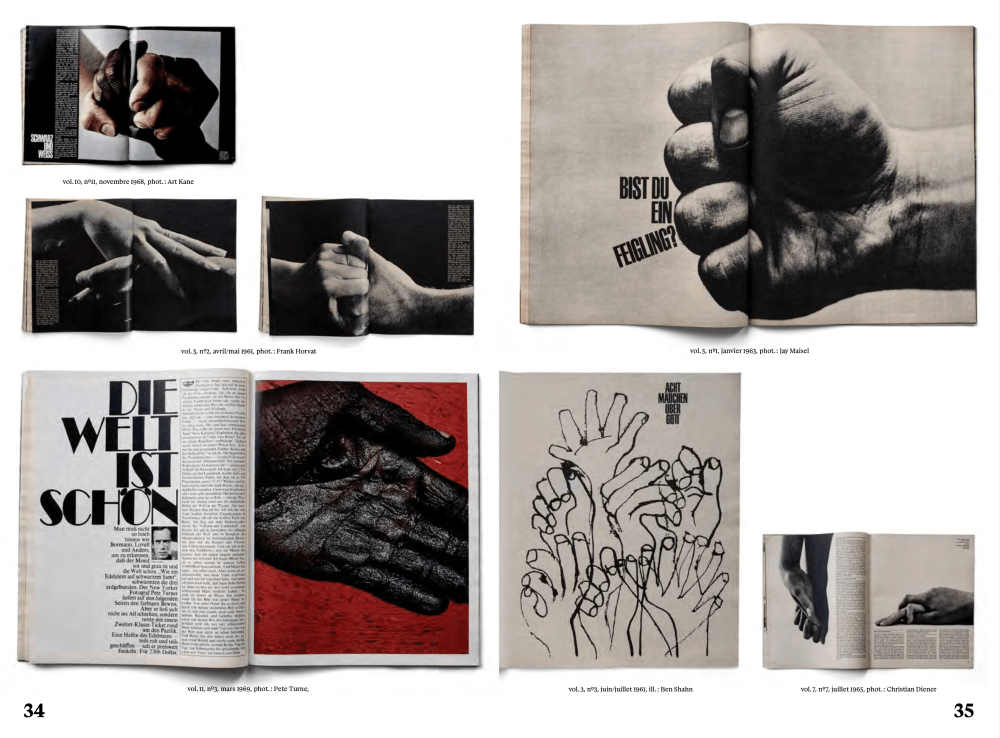

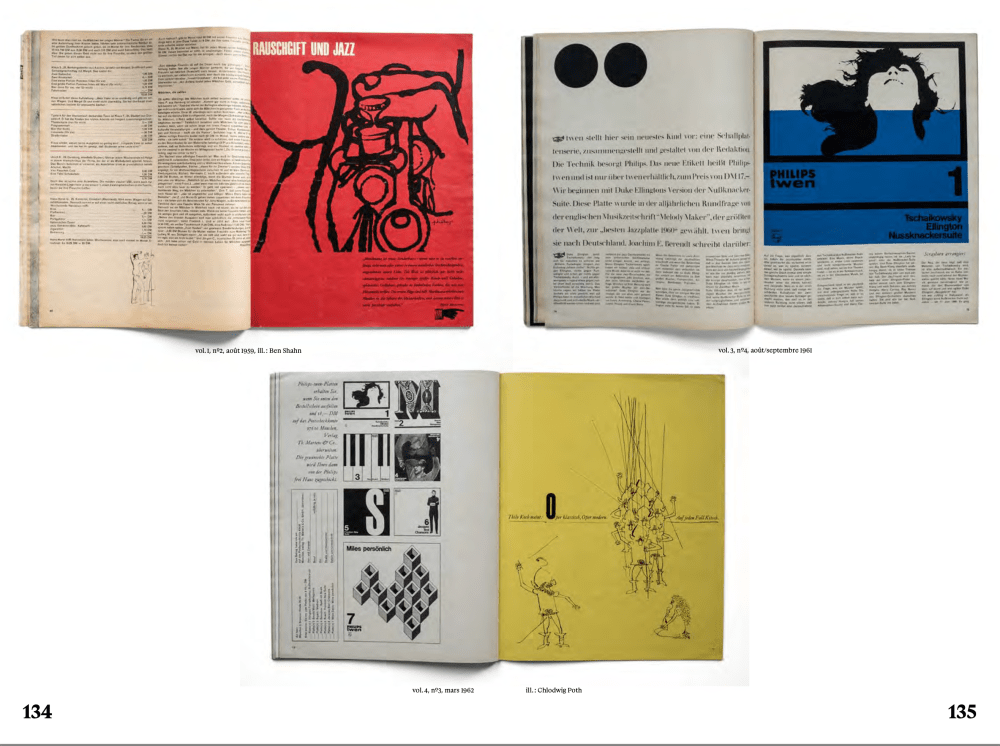

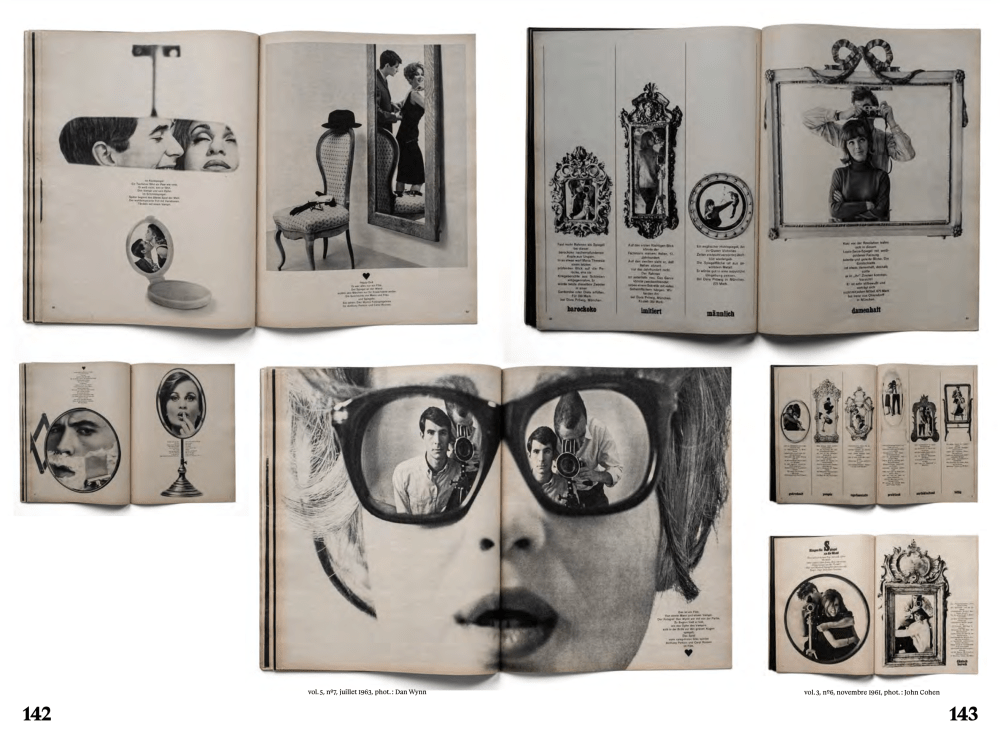

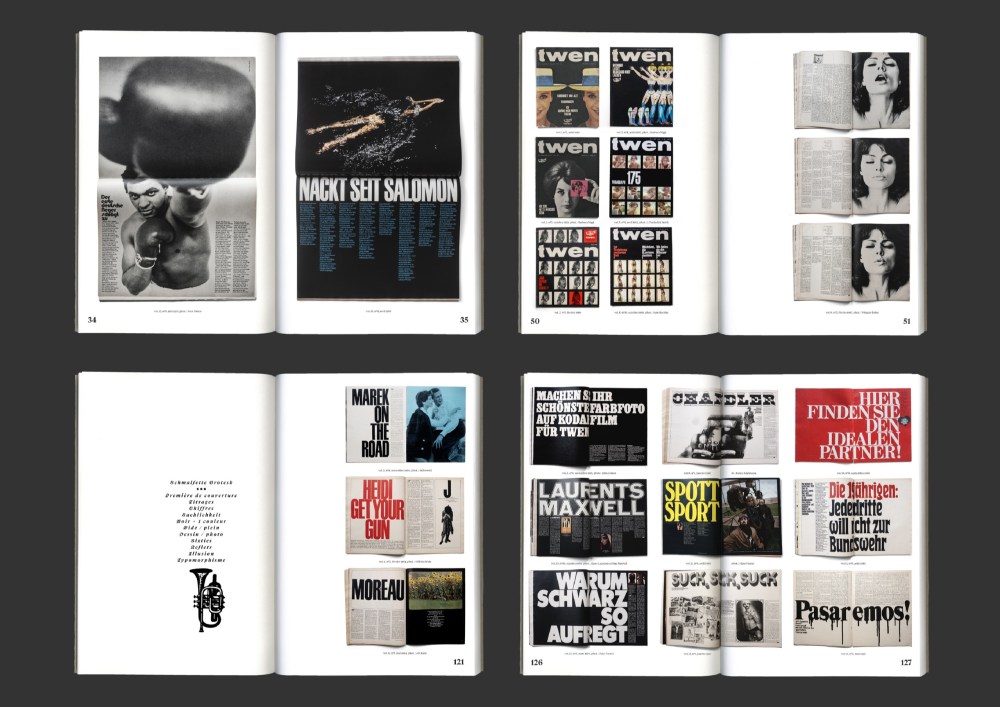

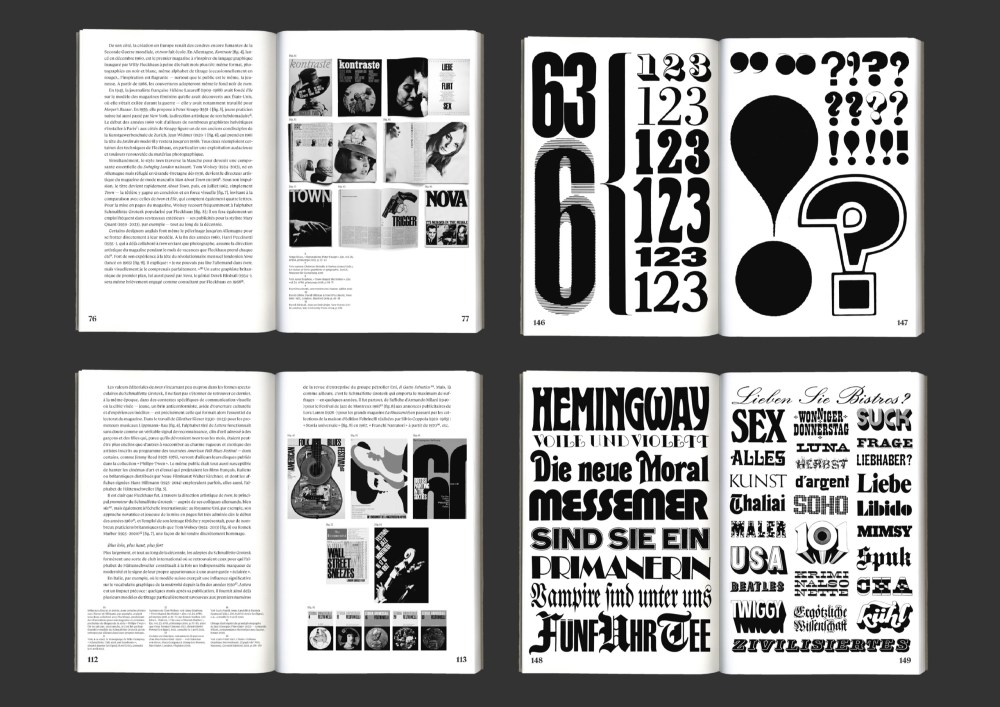

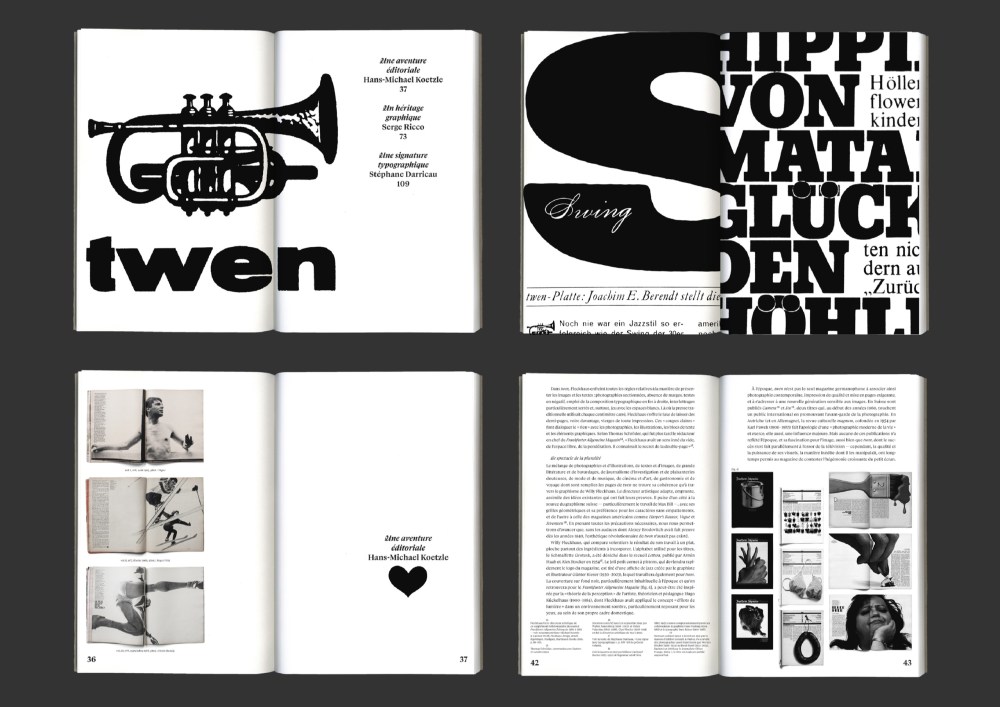

In postwar West Germany, twen‘s luminescence brightened up the creative space in ways that are difficult to measure. Now, a new book, twen [1959–1971] by Hans-Michael Koetzie, Serge Ricco and Stephane Darricau, produced by Bureau Brut, brings its inspiring legacy once again to the fore. Below are some pages that underscore the intelligence endemic to Fleckhaus’ inventive, editorial typography and cinematic page flow.

The following is a translation of a French essay by Hans-Michael Koetzle excerpted from twen [1959-1971] .

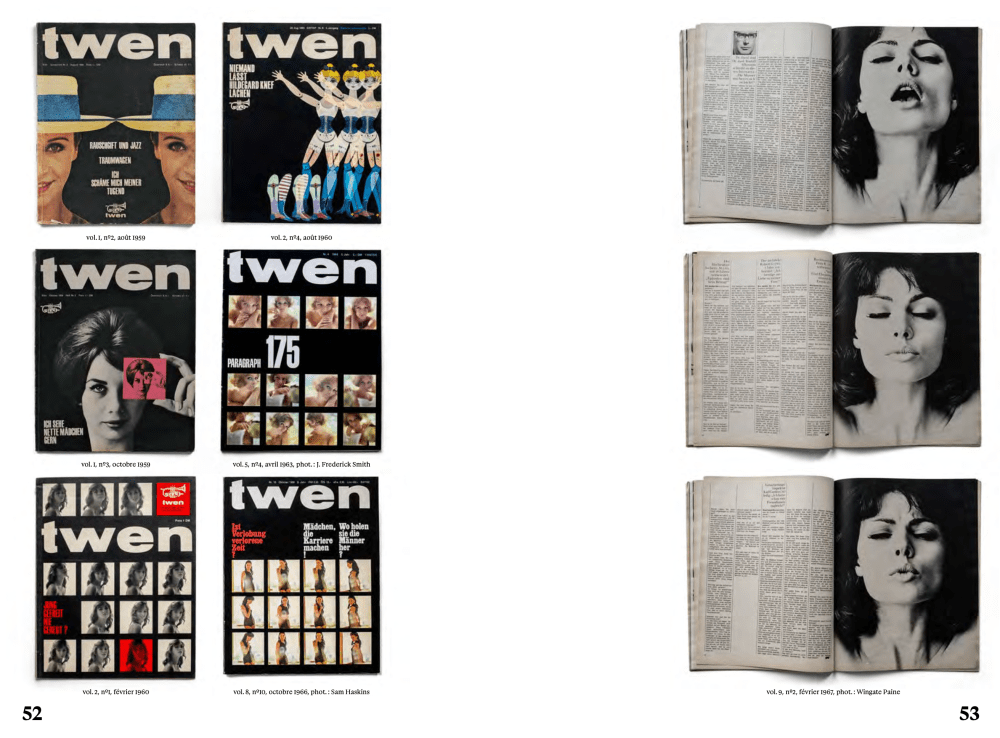

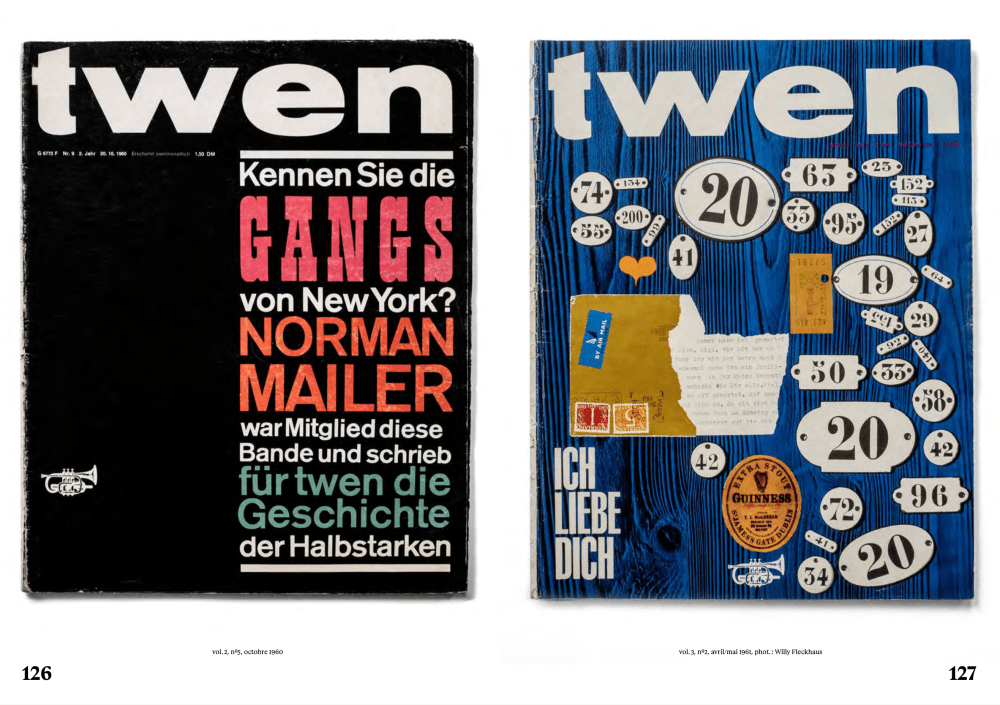

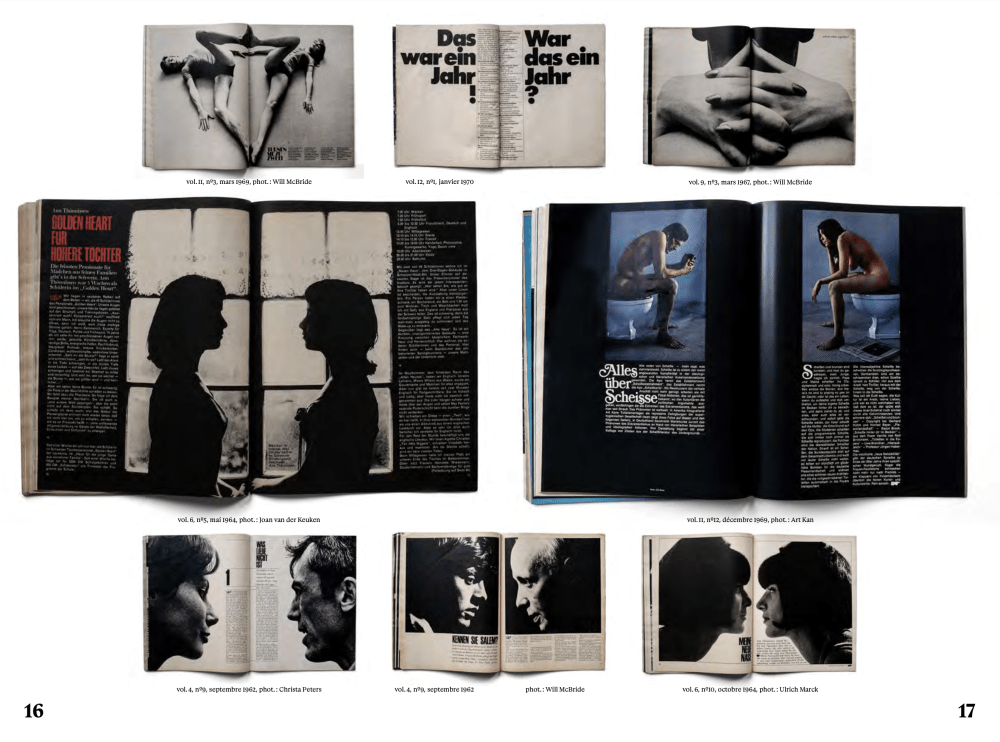

The most influential, and thus the most important, magazine in postwar Germany was called twen. It was published from April 1959 to May 1971 and, although it never sold millions of copies like Stern (Hamburg) and Quick (Munich)—to name but two of the most widely read publications in the early days of the Federal Republic—it did have genuine international reach. It remains the only West German periodical to have attracted a readership not only in Europe but also in America.

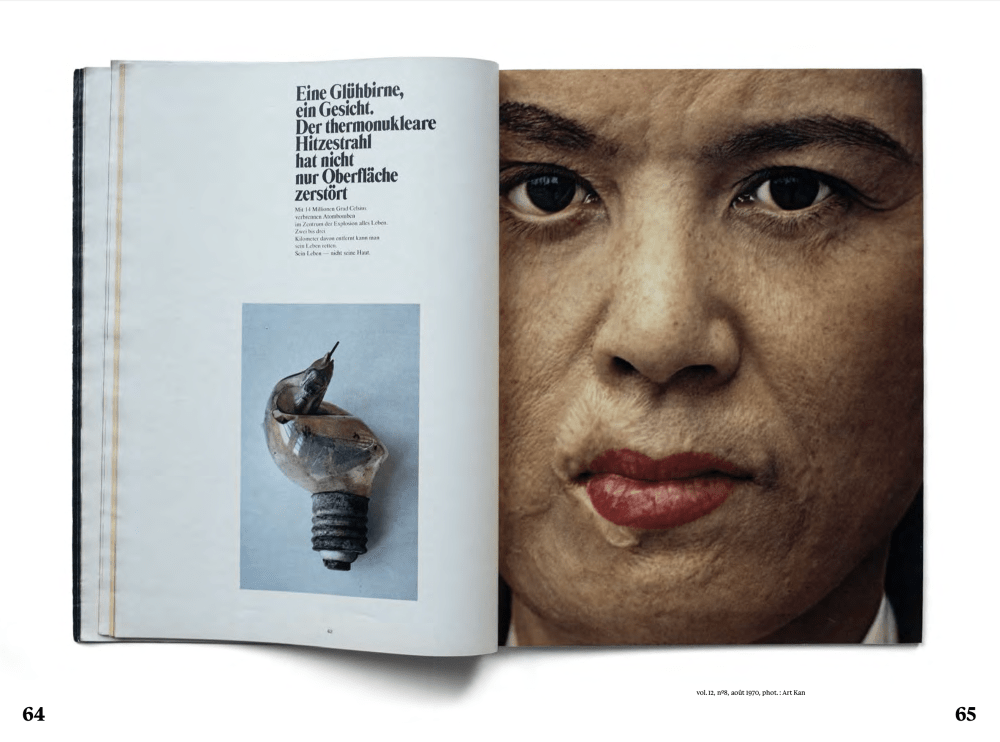

With its innovative photography and spectacular layout, twen set a benchmark for editorial design and, it would seem, still inspires young designers, typographers, art directors and creative types of all kinds today. Avenue and Nova would not have seen the light of day without twen.

… Art director Henry Wolf described it as “the last individualistic magazine,” and David Hillman said it was “like no other magazine, past or future.”

In 1964, Milton Glaser staged a major twen exhibition at New York’s School of Visual Arts, and four years later the magazine was awarded a gold medal by the Art Directors Club of New York. As the editorial of the July 1970 issue proudly announced, this was the first time a European magazine had received such an accolade.

A new kid on the block, twen (“teen”) was founded in the late 1950s by two young Cologne publishers, Adolf Theobald and Stephan Wolf. It started out as a “mere” supplement to the student magazine Student im Bild, which Theobald and his team had been publishing since 1957. The aim of this new project was to reach beyond the campus to all types of young people between the ages of 20 and 30. The title was taken from the ready-to-wear clothing brand Wormland, whose … Twen jeans were hugely popular at the time.

The name was original—a first even for English-speaking countries—and a fresh reminder of young West Germans’ interest in the United States, less than 15 years after the end of the Second World War. Yet, despite the fact it covered jazz, literature, art, cinema, fashion and, first and foremost, photography, all topics of interest to this particular readership, twen was neither a magazine for young people nor a photography magazine, a cultural review or a traditional illustrated publication. It transcended all the usual categories and stood out not only as a magazine that was brazen and provocative, with a penchant for the erotic, but also for its generous and masterful layout.

The first issue hit the newsstands in April 1959 and was 104 pages long with a 36.5 × 27 cm format (slightly larger than subsequent issues, which were all 33.5 × 26.5 cm). It was printed in rotogravure by the long-established printer and publisher DuMont (Cologne), which guaranteed not only production quality but also efficient nationwide distribution. According to Stephan Wolf, the first issue of twen sold out very quickly, not least thanks to the coverage it received from the mainstream press.

(Editor’s Note: Fleckhaus invented the position of the “art director,” which did not yet exist in Germany. He acquired the nickname of “Germany’s most expensive pencil.” This is further explored in Design, Revolt, Rainbow (Hartman Books), the first comprehensive monograph on Fleckhaus. It includes texts by Michael Koetzle and Carsten Wolff, both experts on Fleckhaus’ work.)