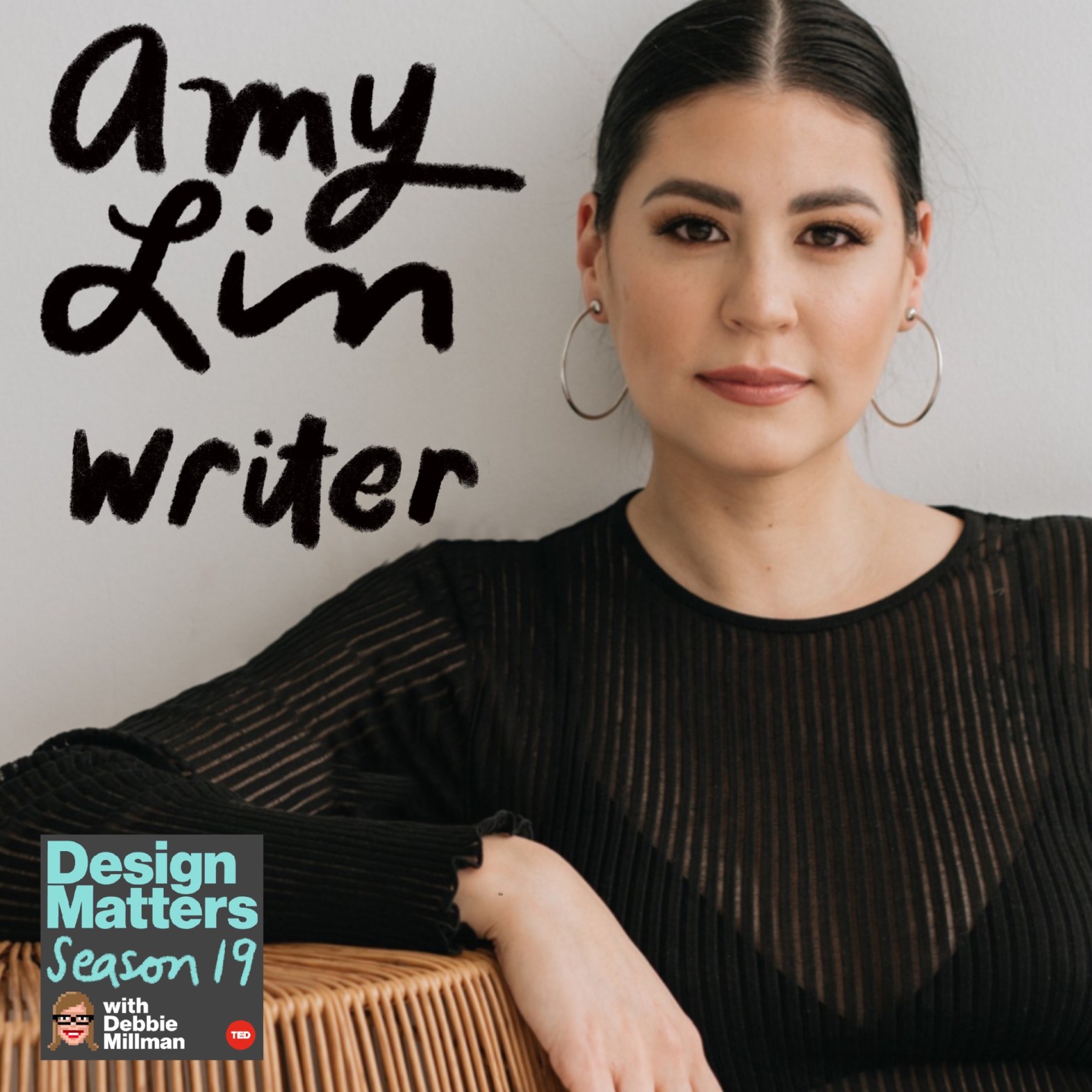

Writer Amy Lin deconstructs grief in her new memoir ‘Here After,’ a beautifully visceral and emotionally intimate depiction of young widowhood. She joins to discuss the science of grief and how she coped in the wake of her inexplicable loss.

Debbie Millman:

My first question is one I’ve been somewhat perplexed as I’ve been living in your life. Is it true that you’ve never tried coffee?

Amy Lin:

That is true. Never so much as a sip, which a lot of people do think is my most psychopathic quality.

Debbie Millman:

That’s what my next question was, and I believe you think or others think that it’s psychopathic.

Amy Lin:

Yeah, I think they just think that you can’t possibly survive if you haven’t tasted coffee. And I will admit that the more people have pressed me, the more entrenched I get in this position to move through the world without it. But I do subsist on caffeine. I just drink green tea almost exclusively.

Debbie Millman:

Okay. You grew up in Calgary Canada where you’ve said that there are two seasons, winter and road construction and where it is so cold, your nose hairs freeze together even in May.

Amy Lin:

Yes.

Debbie Millman:

You speak very fondly of your parents in Here After.

Amy Lin:

They’re here tonight actually. Yeah, this is my parents.

Debbie Millman:

Talk a little bit about your childhood. What was it like?

Amy Lin:

I think my parents adored me, but I was odd. I was an odd child.

Debbie Millman:

Was?

Amy Lin:

Yeah, you’re right. You know what? Am, I am an odd child and I think that’s because my parents always allowed me very much to be the person that I was. I even extremely young would insist upon choosing my own outfits. And I had these very long stories that I would tell as a young child and my parents were extremely patient with this because they really, and to this day, encouraged the narrative making that I’ve always done. Even as a kid, I would have this intense scrutiny of the world and I would watch it and I would narratize a lot as a child. I didn’t realize that people didn’t do this when I was a kid, but I would narrate my life to myself in the third person. “Amy is walking” or “Amy is doing this,” and I was always telling these stories. And part of that is because I’ve always felt, in some way, separate from the world and creating narrative was a way of not only understanding what was happening around me, but also of then finding a way to write myself into the story in a way that I could understand.

Debbie Millman:

And whether my parents understood this explicitly or not, they always understood that story making was essential to who I am. And they always encouraged it. I think I was maybe 10, but I got in my head that I wanted a dog and I was begging my parents, “Please, please, please. I’m the most responsible 10 year old in the world. Please, please, please.” And my parents, wisely, were like, “No, we have enough that’s going on.” And so I thought, “Well, I’m going to show them.” And so I got a stuffed dog and a leash and I thought, “I’m going to act like this dog is real. I’m going to create a story that it’s real.” And I dragged the dog around. It was filthy, covered in leaves and dirt. I would feed it water, I would introduce it to people like it was real. And I thought, “I’m going to shame my parents out of the weirdness of this child into getting me a real dog.”

Amy Lin:

Did it work?

Debbie Millman:

No. When people would talk to my mom and say, “Does she really think this dog is real?” My mom goes, “Amy, just a really rich inner life.” Unfazed and always so supportive of the narratives that I would write.

Amy Lin:

I love that. I think you should get a T-shirt that just says, “A rich inner life.”

Debbie Millman:

I don’t need a T-shirt, Debbie. It comes before me.

Debbie Millman:

So did you write stories about this dog?

Amy Lin:

Yeah, I mean, I just treated it like it was 100% real. I felt that the oddness of that would compel my parents to substitute a real dog, which it did not.

Debbie Millman:

When did you start writing?

Amy Lin:

Young. I have diaries where my mom is telling me five years old, “Yeah, that makes sense to me.” I have these diaries and there’s pages where I write in very ungainly, childish script, painstaking descriptions of myself, “Amy Lin, six years old, brown eyes, hair that my mother cut with a bowl.” Really specific details.

Debbie Millman:

There’s a part of me, Amy, that wants to get your parents up on stage here to include them in this conversation because I’d really love to know what they thought of all of that.

Amy Lin:

Again, they were like, “We love this.” And so I think, in some ways, I can’t fathom who I thought was going to be reading my six year old diaries, but it was really essential to me again, and I think to mirror myself back to me. I don’t think it was for audience when I think about it. I think it was about trying to understand the person that I was. And writing has always been that as a way of accessing understanding.

Debbie Millman:

When you were a young girl, you used to have small anxiety attacks about the idea of eternal life.

Amy Lin:

Yeah.

Debbie Millman:

Why is that?

Amy Lin:

I was weird.

Debbie Millman:

And how do you feel about that now?

Amy Lin:

Well, I actually do think that I thought a lot more about death very young than maybe the average person did, which was not apparent to me truthfully, until Kurtis died, until I started talking to people about death, until I started processing my ambivalence towards living very publicly. When Kurtis died, I am an extremely private person, but I became a very private person with an extremely public pain. And something about that dissonance started causing me to realize that I had really been thinking about death and why people continue since I was very small. And part of that is because I was raised with this idea that when we die, we continue into eternal life. But for me as a child, I couldn’t comprehend this idea that we would want to continue. I didn’t fully understand that. What was so comforting about this idea that there was no end? In some ways, I think the idea of a boundary or the idea of an ending is what brings meaning. Do you know what I mean?

Debbie Millman:

Yeah.

Amy Lin:

And when Kurtis died, I understood both sides of the comfort that offers because as a child U just thought you’re going to keep going and going and going and going. And I would get caught in this expanding. I would literally feel it in my body, this expanding room of consciousness. And I just thought, “How can there never be an end?” And I was too young to understand that I was experiencing anxiety attacks essentially. And then Kurtis died and I started experiencing very serious panic attacks. And I said to my therapist, RJ, “I think I’ve been having panic attacks my whole life.” And he was like, “You just realized this now?” But that was really what connected it for me.

Debbie Millman:

You got your undergraduate degree in English literature and education. At that point, what did you want to do professionally?

Amy Lin:

I wanted to teach. I have always taught in some form. Probably since my early teens, I’ve been teaching students. I used to teach very, very small students learn how to swim. Then I did summer camps. And so I knew that I wanted to teach and I really love to teach. And I think if I wasn’t a writer, I would think that teaching was my calling. It’s just that writing calls me so much more so. I sat out to teach kids, particularly to teach kids how to write and also to teach children that they are not puny inadequate people, that they are in fact fully-fleshed people. Because that was something to me as a child that I did understand about myself, which is that I was very much moving through the world as my own person. And my parents encouraged that.

Debbie Millman:

In your mid-20’s you became a vegan, you dyed your hair blonde, only wore black, not that much has changed. At that point in your life, you’ve written that you couldn’t feel anything good and steadfastly believed that you were not lovable. Why?

Amy Lin:

I never got a dog. They teach you that you’re lovable.

Debbie Millman:

That’s true.

Amy Lin:

They do.

Debbie Millman:

That is absolutely 100% true.

Amy Lin:

They absolutely do.

Debbie Millman:

Absolutely.

Amy Lin:

That’s what I’m saying. That’s what I tried to say when I was 10. How can we trace the roots of our pain? I don’t know when I got it in my head. I just do and it still lives with me. And it’s something that Kurtis loving me as radically as he did was one of the most transformative things because I think when we allow people to love us, part of that work that we have to do when they love us is we must accept that they love us and we limit the love that we have with people if we refuse to change our conception of ourself, if we refuse to accept the ways in which they see us for good and the ways in which they forgive our flaws for better. If we resist that, then we limit how much love we can receive and we limit how much love we can give ourselves and others.

Debbie Millman:

One of the things that I found so interesting about your feeling of being unlovable was at the same time while your loneliness and unlovability had always dogged you, you also had a longing to meet somebody. And so I want to understand if you can share with me the dichotomy between your loneliness and your longing.

Amy Lin:

I think that people, and I include myself in this, that have felt lonely their whole lives, and I have in a lot of ways, are that way because they long. I think longing is so much behind loneliness, that that desire in some way to connect and that sense that there is something in you that wants to connect but maybe doesn’t know the language to do that or isn’t sure if it’s safe to do that or perhaps has tried to and learned that it isn’t safe to do that, only perpetuates more longing. And this constant need isolates you in a lot of ways.

Debbie Millman:

I think it’s about authority. I think they view you as an authority figure and therefore… You had a first date that went six hours?

Amy Lin:

Yeah, it was long.

Debbie Millman:

So was it love at first sight?

Amy Lin:

I mean, it was just that I talked so much and Kurtis was-

Debbie Millman:

Get comfortable.

Amy Lin:

…so kind, he just didn’t know how to escape, I think truthfully. But we did. I just talked and talked and Kurtis later, unknown to me, would write down every story I told him and there were many, but it just kept going. And I felt, and this is so key to why Kurtis and I were the way that we were, was I felt so at ease with Kurtis and it’s very hard for me to feel that way. And I felt immediately as if I did not have to project or live up to any idea that he might have had of me because I could tell that he didn’t have an idea of me and that I could be the person that I was and that there was a softness in the place that he offered me. And for whatever reason, he just stepped to me very tenderly. And it was an invitation.

Debbie Millman:

Your friends told you to play it cool, but you write how you have never known how to love something in moderation. You go on to say that when you were a child, if it was the winter holidays and you were playing board games, you would keep saying, “One more. Can we please play one more?” Until everyone around you would finally say, “No, no more.” If you were basking in the sun, you’d stay out until you were sick. If you were enjoying going over to a friend’s house, you’d want to go over every day. What did you make of this behavior?

Amy Lin:

I made of it a boundary, which was that I always created this narrative, of course, that I always wanted too much, that I asked too much, that I had too much. And so the need then was to limit myself. I needed to learn how to behave more like other people. I needed to feel a little bit less. I needed to ask a little bit less. I needed to learn the ways that people were moving through the world, which was less. And that all of that for me relaxed when I met Kurtis because there was no need to do that. There was no need to limit how much I was asking because it didn’t seem that I could ask too much. And that was what made that time so special.

Debbie Millman:

But it was hard for you. You write about how with Kurtis, no one had ever just wanted you before. He was the first person that you didn’t have to convince, but you don’t share this with him. You’re embarrassed by your own need and you state, you tried to hide its soft yearning with hard demands. And I know what that is, I know what that’s like. What did you do? What tests were you giving him?

Amy Lin:

I asked for things that no one can really promise anyone. I wanted to see around the corner of the universe. I wanted him to say, which he would say, “We’re going to be together for 50 years. I’m not going to leave. I’m going to be here always.” And I ask that a lot and in lots of different ways, often some loudly, some imperfectly, some softly, but I was always asking for that in some way. And Kurtis was always meaning that. That is the legacy of having loved someone who is as big as the sky. Their capacity for love, Kurtis’s capacity for care just continued.

Debbie Millman:

It’s so interesting to me that you were curtailing your needs, curtailing your desires, your longing, but fell in love with somebody that was so unbounded with that love and joy. You tell Kurtis you’re a substitute teacher, not a writer. Why not both?

Amy Lin:

I didn’t see myself as a writer. I was a substitute teacher at the time. That’s what I was doing. It was before I got a full-time job teaching. I wasn’t writing in any particular way and I certainly didn’t see myself as a writer and it would never have occurred to me to say otherwise. One thing I will say about me is that most places I will show up as I am. And so to me I thought, “Well, I am substitute teaching.”

Debbie Millman:

You write about your engagement very beautifully. You write that the feeling that you had was perhaps the only moment in your life where you feel joy and excitement, so clear, so immediate and so intense that you’re not aware of anything else happening. And I believe that you had just gotten out of the shower and still had the towel around you when he was proposing. When did you realize it had fallen off?

Amy Lin:

When I was cold. There was a moment where I thought, “I’m really cold.” And then I realized that I was also naked. That was a moment that I just didn’t limit. And I think it was a moment truthfully that surprised me because I had no preconceptions of what it would be like. And because I had not expected it for myself and because I did not think it for myself and so I didn’t have any time to get in my own way. It really was, in so many ways, Kurtis’s moment that he had planned for me. And again, I think that’s what you do when you love somebody. You give them the things that they’re trying to give you and also to give themselves. And I really gave myself over to that moment and I stopped narratizing it and I just was in it, which is why a lot of it is lost to me, truthfully.

Debbie Millman:

You got married on a beach named Sugar on November 11th, 2018, but after you got married, you began to fear you might get divorced. Why?

Amy Lin:

Because I’m difficult to live with. That’s how I feel.

Debbie Millman:

No, I think it’s more than that. Don’t you all?

Amy Lin:

I also think anytime I really want something, I just think that for whatever reason it’s going to go away and that anything that we really want we can’t hold onto. Even as a child, I was like this. If I got a, let’s say a Sharpie set that I love, the metallic ones, the shiny ones, I would never use them. I would leave them in a drawer and I would think about all the things I was going to do with them, but I would never use them. And if my sister would come in and want to borrow them, I would, “No, those are for a special occasion.” And then they would dry up and I would just always hold onto them because I couldn’t bear the idea of things ending, especially if I loved them and especially if they were precious. And so when Kurtis and I got married, I just immediately started thinking about, “Well, something this good has to end. Of course it will end.”

Debbie Millman:

You struggle in the relationship as you realize that there are two yous simultaneously existing, the person he thought you to be and the person you knew yourself to be. And most of the time you wanted to try to be the woman he believed you were, but you were not really her. And it seemed to me, Amy, that he always loved you for exactly you and not someone he had constructed. Looking back on it now, do you still feel that he loved a version of you?

Amy Lin:

I think that Kurtis always loved people on their best days, and he got this idea of them on their absolute best day and decided that that was the fullness of who they were. And I think that’s a beautiful gift to give somebody to mirror back to them who they are, even on their worst days. But part of my understanding of love and my belief about love is that we have to hold the fullness of the people that we love. And the reality is we are yes, our best days, but we’re also our worst days. And that there is a part of me, which is where God keeps the knives. I’m the knife drawer sometimes, that’s just the reality. And that was something that Kurtis would refuse about me, that there were no knives and in his world, there were none. And I needed him to acknowledge that actually there were, and actually a lot of them lived with me.

Debbie Millman:

Well just maybe sharp edges.

Amy Lin:

Yeah, and that’s something that Kurtis would argue was, “Oh, well, yeah, okay, so sometimes there’s this, but it’s not that.” And I think I just needed him to see, but sometimes it is that. That’s the reality. And all of us, if we’re really honest with ourselves, have the ability to pull out a knife. That is the reality. And I know that about myself and I’m not blind to that. And I needed Kurtis after our years together, I just needed him to see that. I knew that he would love that. I already knew that, but I needed him to see it. And that’s a complex thing to ask somebody and difficult.

Debbie Millman:

On August 15th, 2020, your life changed in an instant. Kurtis was 32 years old, he went out to run a half marathon with your family and he collapsed mid marathon and died instantly as he hit the ground.

Amy Lin:

Yeah, before actually.

Debbie Millman:

Before he hit the ground. I’m really sorry, Amy.

Amy Lin:

Thank you.

Debbie Millman:

I called Amy before the podcast, which I never do because I was so concerned about how to talk about something so horrific and so tender. And so if there’s any questions that I ask you that you don’t want to answer, please just say, “Pass.” Kurtis’s heart stopped very suddenly. It’s considered an out of time death. That’s the phrase as it remains unexplained. And you were plunged into acute grief, you stopped eating, you stopped sleeping. You sent your therapist RJ a one line email telling him what happened, and he called you immediately. What did he say to you?

Amy Lin:

He said, “Do not grieve alone.”

Debbie Millman:

Why?

Amy Lin:

Because he knows me. Because I was already preparing to just go into the prairie and lie down and just become with the earth. It’s always been my way. I’m very private. I’ve always processed privately and I think he knew, my therapist is religious, he would say in a divine insight, I know that he would say that, that I was going to need help. And I don’t typically ask for help. And I think he knew that I was in clinical shock, but I think he knew if I’m going to get one thing in through the door, it needs to be don’t grieve alone, connect with other people.

And one thing that speaks to the trust that RJ and I have is that I really listened when RJ speaks. And that was a trust that was hard won. And he will say, because he said it to me before, he said, “I felt like you watched me for the first three years of our relationship. In all the sessions,” he said, “I thought not that you were there so much as you are watching me.” He felt observed. I don’t do that intentionally, but even as a child I would observe things and I realized that I did. I probably did observe him for that long to decide if when he spoke I was going to listen to what he had to say. And so when Kurtis died, we were past that. I already knew that when he spoke I was going to hear him.

Debbie Millman:

He told you that you couldn’t survive alone, but you told him that you didn’t want to, that you were looking for a place to die. You found a mountain called Nameless and a lake called Disappointment. What was his response to you telling him that?

Amy Lin:

He said, “Well, where did you find those places?” And I said, “Google Maps. I’m just Googling.” To which he just nodded. And that’s the great thing about RJ. It’s the great thing about having a trust bond with your therapist is there was no commentary there because he also knows certain points where there are no fly zones with me. And it was a no-notes time. And so he just wanted to know the provenance of those places. And we moved on.

Debbie Millman:

You read a lot of material about what it meant to be a widow and the ramifications. Statistically widowed are two and a half times more at risk of dying by suicide in the first year of widowhood. You also read that you’re 22% more likely than the married to die of other causes such as cerebral or cardiac events, cancer, car crashes. And while these illnesses and incidents may seem random, they’re not. And I’m wondering if you can share a little bit about why they’re not really random.

Amy Lin:

So obviously the suicide risk is because when we have out-of-time death, but really when anyone experiences traumatic death in this way, it causes you to ask questions that lots of people spend a lot of time avoiding. Why are we alive? Why should we continue? How much pain can someone hold? How much pain should you hold? How much pain do I want to hold? These are big questions that take you to the edge of the questions themselves. And when you get there, when you push the questions far back enough, then you are confronting a kind of mortality. And for a lot of people there is no one at the edge there. And you make a decision.

In terms of why the widowed are more likely to die, quite frankly has a lot to do with the fact that grief is not only an emotional trauma, it’s a physical trauma. And so we know that when people experience loss like this, the blood that goes to the front of the brain, which is doing communication, it’s doing memory, it’s doing impulse control, that blood gets diverted to the back of the brain which is doing survival. So it means when you are trying to remember the time that you should be at the doctor’s office, you are going to have more difficulty remembering that because you literally have less brain resources dedicated to memory. It means when you go to cross the street, you aren’t actually going to as accurately gauge whether that vehicle is traveling too quickly to stop because the part of your brain at the front that does risk assessment is offline. It’s not being served at this time.

And so the widowed, they tend to take more risks without realizing it because that part of their brain for a long time is not being physically served. And that’s actually what contributes to this data, which is that even unthinkingly, the widowed, they take more risks with their lives. And also because when someone dies, grief puts so much of what they call the stress chemicals into your body, it jacks them up so high and sometimes for 5-10 years, because acute grief is the first five years and then you enter chronic grief, but you have all of these chemicals, these stress chemicals in your body for at least five years and it’s suffice it to say, not great. That contributes to a lot of disease. It makes you literally vulnerable at a cellular level to more disease.

And so in so many ways, grief threatens your life from risk assessment to disease and then of course to having to confront the questions of why anyone should be here. And that’s all something I read in a haze after Kurtis died, which is shocking to realize and to understand, especially when you are very young. It’s very humbling to understand that so much of our bodies are deciding for us and we would love to participate in this idea that we are deciding. But at the end of the day, Kurtis decided nothing. His heart decided, his body decided. And something that trips me out about that because the body is the only given thing, the only thing that’s given to us. Everything else, all these systems of power and attachment and thought go behind things that we receive, but the body is made, the body is actually given and then the body takes. And there’s something about that reality, that dissonance that is unsettling to live in.

Debbie Millman:

Oh, absolutely. I mean, it’s amazing to me that it’s the reptilian part of the brain that also gets ignited with the cortisol when you go through a trauma-

Amy Lin:

Yes, absolutely.

Debbie Millman:

That also controls your eye blinking and your digestion and your metabolism, your adrenaline, and those are all things you can’t will to happen. You can’t say, “Okay, stomach start to digest now.”

Amy Lin:

Exactly.

Debbie Millman:

You are at the mercy of your own body. Speaking of which, two weeks before Kurtis died, you fell off a scooter and injured your knee. 10 days after Kurtis passed, you almost die from a series of blood clots in your legs. You also have pulmonary clots. Now most people presenting with deep vein thrombosis which is the technical name of what you had, are over 40 years old. Do you feel that the shock of Kurtis’s death ignited this event in your body?

Amy Lin:

Well, the answer that I have from the many physicians that have looked at my super clotting episode is that I’m unlucky to which I say, “Duh, obviously.” And so when I fell off the scooter and I injured my knee, they think that I had a trauma clot at the site. Okay, not great, but not necessarily life-threatening. But compound that with the fact that I have a pre-existing condition that’s almost impossible to diagnose, which is May-Therner. So there’s a pinch point where I had a clot so old that my body had already just compensated for that. So now we have two pinch points, both of which where there are clots. And then in between, it’s all fine until I stopped eating and I stopped drinking for so long, which of course we know will thicken the blood and all of this combined, they think created this super clotting event, which is to say there are a million ways I could have lived where it wouldn’t have happened to me, but that was the way things fell. And I think it’s just bad luck truly.

Debbie Millman:

You end up in the hospital. While there, you write how part of your brain was screaming, your life is at risk. One part of your brain was telling you to do what you could to live. And since it had been only 10 days between Kurtis’s dying and you nearly dying, you think if you go now, you can still find him. He might even be waiting for you. What other part was telling you to stop trying to live that was overcome by deciding to live.

Amy Lin:

It’s so odd to be in that space and my parents would know, they were there, I kept asking my dad, “Am I going to die?” Which again, I was in shock on so many levels, but to be, I think of my parents, to be the recipient of that kind of question is so awful. I think worse maybe even than being the asker of it. But I was really trying to understand that and I was trying to weigh if that was a good thing or if that was a bad thing. Because my whole life, I’m always trying to think my way through all my problems. That’s what I have. I’ve always been able to think my way through all of my problems. And that’s part of what is so humbling about grief is you actually cannot think your way through it. It’s so Leviathan, it’s so encompassing that eventually you will reach the end of how much you can think about it and then you have to start feeling about it. And that’s where the experience of grief starts to bifurcate you if you can’t accept that reality.

And so in the hospital, I was trying desperately to find a way to hold both pieces of that together, the feeling and the thinking, and to try to understand what I wanted to do. At the end of the day, I decided to continue because my parents were there. They were there in the hospital, which is amazing because it was in the middle of a pandemic and nobody was really allowed in the hospital. And that’s a testament to the kindness of the people who worked there, that they allowed my parents to be there, that I was not alone in this hospital in the middle of a global pandemic.

And as I’ve said before, I believe that our burden, if we are going to love people, is to accept their love when we don’t really want to. And I understood even then, even in the haze of trauma and shock that my parents wanted me to live and that if I loved them, I was going to try to do that. That that was the most important thing. And I’ve said this before, but that’s the best thing any of us can offer anyone is to witness them and to love them and to be there, to be present for them. And in so many ways, witness has saved my life. That was just the first instance of it in that particular moment.

Debbie Millman:

You began to see a grief counselor who told you that the fight or flight sensation that you were experiencing begins to ease around six months. But in month six through nine, emotions heighten and diversify and those months could end up feeling worse than the first months. So this information stated that normal acute grief lasts four to six months before beginning to lessen. But did the material explain what normal grief is?

Amy Lin:

I mean, I think it’s not a secret that I did not love my first grief therapist. And I did press that point, “Well, what’s normal grief? What’s acute grief? What’s chronic grief? What are the differences?” And she didn’t really have any answers for that. What she really was trying to communicate to me was that as bad as it was then, it’s going to get worse. That’s what she was trying to tell me, that the fullness of my emotional range was not yet back online. And she was, in her own way, trying to prepare me for what that would be like. But I wasn’t ready to receive that. And what’s more, I wanted some answers and she wouldn’t give them to me.

So the answer is still, I remain a little bit confused on what that is. And I think it is a point of misunderstanding in grief studies of confusion because I continue to ask people this question, “So normal grief, what is that?” And all grief therapists that I’ve spoken to will say, “Well, there of course, only grief is so unique to each person.” I’m like, “Well then why do we persist in using this term? What’s normal grief?” What I think they’re talking about, if I was to hazard a guess is they’re speaking about the biological stress in the brain. I think that there’s a massive chemical shift that starts to kick in around four to six months, that the reptilian part of your brain starts to think, “Okay, well we can’t be in this state forever.” And I think a physical change that starts to happen and I think that’s what they’re talking about. But then let’s not use the term grief because people think you’re talking about an emotional state. Grief is also physical, but people don’t understand that. So let’s talk about the physical in language that they understand.

Debbie Millman:

You asked your grief therapist if there was an amount of time, and I did that too. 20 years ago, I had a very sudden divorce and I was catatonic. And I remember asking my therapist at the time, “How long am I going to feel like this?” And she was like, “Probably around two years,” and I’m like, “Two years?”

Amy Lin:

I know. I know.

Debbie Millman:

And it was five. It ended up being five. But if she had told me five years then-

Amy Lin:

You would have just Kool-Aid manned your way through the wall.

Debbie Millman:

…I would’ve gone through bridge you were looking for.

Amy Lin:

100%

Debbie Millman:

So you gasped when she told you it might be three to five years. You then went into a specialized grief therapy, a grief therapy which you undertook at the Bob Glasgow Grief Center in Calgary, which is the only one of its kind in North America. There you learned, and this part was astonishing to me, you learned that the five stages of grief that we’re all taught about, denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance were never meant to describe the experiences of the bereaved. Those stages arose out of a non evidenced based study that considered the emotional experiences of people diagnosed with terminal illness. So the five stages that we’re socialized with-

Amy Lin:

Absolutely.

Debbie Millman:

…were meant for another kind of pain. I found this astonishing. I had to put down the book for a few minutes.

Amy Lin:

Listen, so did I, and if you read even more about it, the woman who headed that study has openly said, I think pretty much to anyone who will listen to her, “I never intended the five stages for the people who are bereaved. It was about studying people who were diagnosed with terminal illness. What did they process? How did they process it? Can we categorize the arc of their metabolizing of their experience? But somewhere along the way it got universally applied,” and there seems to be no universal footnote to that. I was just as gobsmacked as you were that those stages don’t apply.

And even a quick search on the internet will produce so many articles that tell you that they in fact do apply to you. So that’s confusing as well because if you’re not paying extremely close attention, you’ll just read the first thing that Google returns to you, which often is a website telling you that eventually you are going to do some yoga, wheel pose and you’re going to be in acceptance, which is so false and so harmful to people that are grieving. And it’s also very hard for people who are grieving to pay very close attention. How are they to know?

Debbie Millman:

One thing I really was so grateful for learning in your book is that grief is really considered chronic pain. And you ask a question, I want to ask you, how can grief be so universal and yet so widely misunderstood?

Amy Lin:

I think that art at its best asks questions until it reaches an unanswerable question. And often when I consider work, I will think about the questions that it asks me and think about if I ever get to a question that I don’t know how to answer. And so when I wrote that question, I wrote it because it was the question that when I pushed all the other questions, it was the one that I arrived at. And I think my answer to it would be that we have no language for the grief that we are all in and we have no particular vocabulary or grammar. And grief has its own grammar. That’s the thing. Grief is its own language. And so few of us have any models for it, and so few of us have any teachers of it.

And what’s more, all of us are carting around our really good intentions, which are that we don’t want people to be in pain. We want to make them feel better. And that’s a really good place, but it’s really dangerous for people who are grieving. And I think that’s how we get there when we don’t have a language for it. And what’s more, what we do have an overabundance of language for is how I can make you feel better, the happy clappy. And so everybody leans on that and what’s more, the thing that they don’t have words for, it’s very uncomfortable to go into that place. And when you don’t have any guides for it or any mirrors for it, it’s very unlikely that you’re going to go slashing into the forest by yourself.

Debbie Millman:

You deconstruct the question, “How are you doing?” And you talk about how you get particularly wrangled when people ask you how you are or assume you’re doing better because you were able to get out of bed or put on some makeup and you think that what it is that they’re really asking, and you create this list about how you could respond. Do they want honesty, assurance, platitudes to share their own story if you reciprocate as you feel you ought to access details that might not be welcomed by way of this inquiry? And you actually wonder if they’re actually asking about your grief or your physical ailing body or both. Why are people so afraid of grief in others? I can understand why we don’t want to have grief in ourselves, but why are people so closed off to being able to manage or handle or experience or witness other people’s grief

Amy Lin:

Because they’re not taught to do it. It’s so wild to assume that someone who’s likely never been told, it’s actually okay to sit with someone who’s in pain and not provide some kind of answer. It’s really rare person, and I have a couple of friends actually that are almost divinely possessed of this gift, which is the ability to sit with someone’s pain and feel no need to diagnose it or change it or make it any better and to just witness it. And so people do come by that honestly, but they are quite rare and it’s more likely that people want to move through it or make you feel better. And so they’re afraid of it because when you sit with someone who is in a lot of pain, it’s painful to you as well. And it’s really hard to see the people that we care about, to see them ail. And it’s so difficult to accept this dichotomy, which is the best thing you can do for someone who’s grieving is allow them to be in pain around you and that that is healing, that witness is healing.

And that’s very hard because you are to be in pain as well, and you have to confront what your capacity for pain is, what you are willing to do. And when you sit with someone in grief, you have to then also sit with your own pain, your own grief at their sadness. And that’s where I think it gets very sticky for people, whether they realize it or not, because they begin to look at how much pain they would like to be in and who really wants to do that? And then you start having to see how much water you want to carry for the people you love. That’s what makes people uncomfortable, especially once you go there. If you have grief that you haven’t processed, then you’re swimming in waters without a lifeguard on duty and that’s very scary. And on top of that, someone else is in the water with you.

Debbie Millman:

Another thing I learned from your book is that statistically most grievers will lose their support base at about a year, if not before, because the enduring state of sadness causes people to disconnect and other people can’t handle how sad you are and think you’re not getting any better. People report that year two is so much worse than year one because the support you had from friends and family often goes away. Life goes on for those people, but not for the griever. What would you tell anyone who has a friend or a family member that is grieving about how to engage with the griever?

Amy Lin:

I would tell them that I think people often disconnect because of what I just talked about, which is that they can’t witness that much pain. But I think there’s, again, this idea that we have to see everything and we need to be everything to that person. But I have friends that still to this day, they text me on the 15th and it has been so many 15th’s since, and they still do that. And after Kurtis died, they sent me a card and then they would text me on every 15th. And that’s what they’ve done for three and a half years, which is incredible and so steady and so manageable and so holding in so many ways.

So I would tell people, you don’t need to do these big things. You don’t need to hear everything. You don’t need to do hours of mutual support. You just need to do something that shows that you are witnessing and whatever that thing is, if you can continue to keep doing it, all the better. And I was told this often in grief therapy, which was start smaller. I have such an all-or-nothing approach to everything. And my grief therapists would say, “Just start smaller. Don’t start with you’re going to go for a half an hour run. What you’re talking about? You need a walker to get out of bed. Start with two minutes with the walker around the house.”

It’s the same when you support people in grief, start small, start with what you can offer. If it’s too vulnerable or too painful or too triggering to sit with someone for three hours, call them and speak for three minutes and then say, “Okay, well I’ll call you tomorrow.” Most people can do that, but because we talk so little about grief and we have so little language for it, people have this idea that somehow they need to be load-bearing for you all the time. Nobody can do that. No one could stand up to that.

Debbie Millman:

All of this that you’re experiencing is happening during the pandemic, so you’re also in isolation at that point. You’re therapist actually directs you to start writing about your grief. What did you think of that idea?

Amy Lin:

I thought that was stupid.

Debbie Millman:

But you did it anyway.

Amy Lin:

I did because I trust my therapist and he never pushes any points, but he pushed this one as hard as he has ever really pushed anything. And he said, “If you’re not going to tell people about it, then you need to write it down.” And I thought about it, and he was very insistent on this point. It was like, “Write this down or pick someone to call.” And I really didn’t want to call somebody. I did not want to speak to someone face-to-face, face. And so I said, “Okay, then I’ll write it.” And I started a Substack, which is a newsletter, and it was relatively unknown. It feels much more common to me now, but it was relatively unknown when I started and I made it public, which really concerned my therapist. He felt that it would open me up to commentary that he wasn’t sure I could manage.

But I was just so supremely convinced in my obscurity. I was just like, “Well, my mother is going to read this.” And I really wanted people to be able to opt in or opt out because grief is so all-encompassing. And I wanted people to be able to choose how much they saw or held. And one of the beautiful things about the Substack was that so many people chose to read it every week, which was shocking to me and not shocking to my therapist.

Debbie Millman:

You started the newsletter, the Substack titled At The Bottom of Everything on September 15th, another 15. Yet for the first year after Kurtis died, you were unable to read.

Amy Lin:

Years, multiple.

Debbie Millman:

Years?

Amy Lin:

Yeah, I would say almost three.

Debbie Millman:

You’re a writer. Your Instagram is Literary Amy, where you post photographs of the books that you’re reading and it’s like three a week. I mean, you stopped.

Amy Lin:

Entirely. Yeah, I would say in a knife fight between being a reader and a writer, I would choose reader, but by a very small margin and only if I had to. So to lose the ability to focus, and I really did lose the ability to read, was just another thing that I felt grief had robbed me of. And if you had asked me this question, even in December of last year, I would’ve told you that it just was never going to be returned to me. But sometime around mid-January of this year, I picked up a book and it wasn’t painful, which of course I immediately panicked that I was experiencing some sort of stroke or I just thought, “This is it for me. They’re giving me the final dinner before they take me out.” And I think it’s just a part of the physiology of my brain is starting to come a little bit back online, but it’s so odd to be without something that normally sustains you entirely.

Debbie Millman:

Did the writing help bring you back to the reading in any way?

Amy Lin:

No. The reading had to come back on its own time and in its own way. The writing was all about processing and reading for me is not so much about processing so much as it is about understanding. And I think maybe you need a kind of perspective to be able to read and a kind of empathy, certainly to be able to read.

Debbie Millman:

Well it makes you feel a lot.

Amy Lin:

Yes. And when you’re in grief and when you’re processing, so much of your empathy is self-focused. You’re trying to hold space for yourself, and I just don’t think I had those resources. But in writing, you’re trying to understand and when so much of your empathy is directed at trying to hold grace for yourself, that does serve writing because empathy will always open writing.

Debbie Millman:

Your new book, Here After evolved out of the writing that you were doing online. How did the book come to be?

Amy Lin:

Well, I lied to my agent. Came from a lie. She asked me about two years into the Substack, which I still write, and she said, “Well, do you think in all this writing you have a book?” And I knew that I didn’t, but I said I did because I feel this constant need to be the best student in class. And so I felt like I would be letting her down truthfully if I said no. And so then after that, I panicked and I went into the Substack and I copied all of the letters and I put them in a Word document and it came to 110,000 words. And I thought, “Oh, thank God. That’s a book length. Okay. I didn’t lie. I didn’t lie.” I was like, “Okay, it’s going to be okay.” But then I started actually reading the letters. And the thing is, the Substack began as a project, which happens organically. That’s what projects do, they happen to you. But books are made and those are two very different things.

And so I realized I didn’t have a book, I had a project that was 110,000 words, and I thought, “Oh, well, this… I can’t have lied to my agent who I adore.” And I began to try to find my way into a book. And it really wasn’t until I started making these text boxes in Word, which are these small boundaries, and you can only fit so much text in them. And I made one for every page of which I had hundreds. And for every page I would put all of the text into the text box and I would read line by line. And if I didn’t feel that that line was something I had to keep, I deleted it and I would only keep these very small cubes. And once I did that for about three months, I began to see this very bright bone of grief, the essential part of my experience. And that was when I knew that I did have a book that I wasn’t in fact, making a book.

Debbie Millman:

The narrative arc of Here After is really beautiful. It doesn’t move through time in a linear way, and it’s all written in the present tense. What made you decide to structure it in that way?

Amy Lin:

A couple things. The present tense came, and it was a point of contention, not strong contention, but during the editing process that it was all in present tense. But the thing about grief is that for me, it completely shattered any sense of time. And when Kurtis died, what was technically past tense, wife, marriage, future, felt so much more real to me than what was present tense widow death, the unknown. And that’s emotionally true, but it’s also physically true. The brain has not yet caught up to the physical reality of what has happened. For the brain, the neurological under understanding of Kurtis, wife, marriage is still very real. The neural pathways are very active.

And so grief makes everything present tense because the past is more real than what’s happening. And then the way in which the narrative fragments and braids and leaps is because grief doesn’t answer to our narrative idea of time. It has no interest in that. And I was constantly seasicking between memory and reality, and I was coming in and out of these ideas of who I was and who I was not and what’s more, I didn’t want this idea in the book that Kurtis was over there and then I was over here. Kurtis remains so present to me, remains so clear in so many ways to me. And I return to him so frequently throughout my days. And I look for him so often where I go. And I wanted readers to do that, to have that experience in the book that you might turn the page and there Kurtis would be, and you hope it, because in my opinion, Kurtis is the brightest part of the book and you’re always sort of hoping that he’s on the next page.

And that’s what grief does. It takes you in and out. It takes you in and out of this hope that you’re never going to get an answer for. And I needed the structure to feel that way. It felt that it had to mirror that, and I wanted to mirror that to griever’s like, “No, you haven’t lost your mind. This sense of here and then there somewhere totally in between is actually in fact what’s happening to me too.” And I wanted the book to feel that way. And some people really love it, and some people, as I just recently read on Goodreads quote, “Really hate it.”

Debbie Millman:

Well, my wife, Roxane Gay, who’s a writer, always says to anybody that talks about Goodreads, “Do not read the reviews.” My last question, at the end of the book, you go on a writing retreat and you attempt to ride a bicycle, something that you were afraid to do given the number of times you’d fallen in the past. Kurtis loved riding a bike and you decide you’re going to try. What made you decide to try again?

Amy Lin:

Well, part of it was the pool could only be accessed by bike.

Debbie Millman:

So it was just a practical thing.

Amy Lin:

Yeah, so much of my courage really is a practical thing, which is that when I was at this writing retreat, upstate New York was in the middle of an absolutely punishing heat wave. And I, because I was new to the retreat, did not know as all the other residents did, that you have to ask for the studios with AC. So I didn’t ask for it. It’s a very old mansion where I was staying, and I got put in what was historically the servants quarters and there’s no AC and the windows are sealed because the bats fly in at night and I was sweltering and everybody who got on their bicycle and cycled to the pool returned looking remarkably refreshed. And I too wished to be refreshed because it was so hot.

And this is the beautiful thing about grieving and loving somebody is that when you live in it for a long time, sometimes, not all the time, but sometimes you can access a tiny bit of their courage and their bravery and who they were. And I just thought, “Okay, one, I am so warm,” and my temperature regulation is very important to me. I do not like to get too warm. I don’t like to be too cold. I really want to be the perfect temperature all the time. And I just thought, “Okay, Kurtis wanted me to do this thing. It’s not far. He was always telling me that I could.” And I thought, “Okay, I’m writing this book, I’m going to be brave.” And that’s the funny thing about bravery is somebody tells you for long enough that you can be brave and there isn’t any soundtrack when you do it, you just one day you get up and you just do it. And so I did. I just got up and I thought, “I am so hot. And today is the day to be brave.”

Debbie Millman:

Amy Lin.

Amy Lin:

Thank you both so much. Got to go.