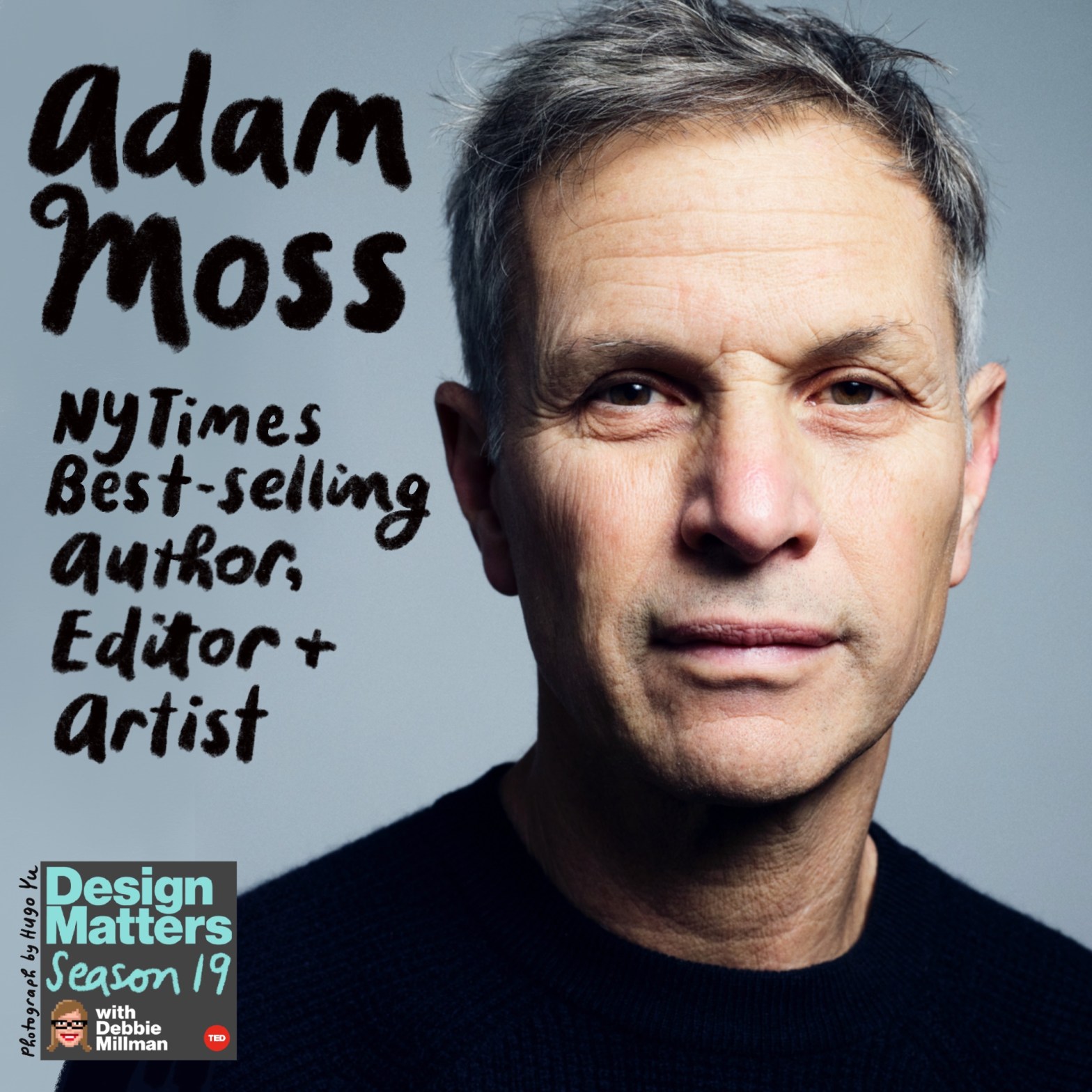

Adam Moss is widely known as one of the great magazine editors of his generation, remaking and reshaping The New York Times and New York magazine into the most significant print and digital publications of our time. He joins to discuss his illustrious career as an author, editor, and artist.

Debbie Millman:

How does something come from nothing? How do creators actually create? These are the questions Adam Moss has long been asking. They also happen to be some of the questions that I try to investigate with every guest on every episode of this podcast. How did you become you and how did you make that? Adam Moss is the former editor of New York Magazine, and before that, he was the editor of the New York Times magazine. He has left an indelible mark on those magazines and on the many others he’s worked on. Adam Moss is also an artist. He came late to the fine arts and he’s a little reluctant to call himself an artist. We’re going to talk all about that and how he wrote and created his brand new book, The Work of Art: How Something Comes From Nothing. Adam Moss, welcome to Design Matters.

Adam Moss:

Thank you, Debbie. Glad to be here.

Debbie Millman:

Adam, I understand you have really tiny handwriting.

Adam Moss:

Yes, I do. Do you want to see it?

Debbie Millman:

Was it always really tiny, or did that evolve from your work as an editor?

Adam Moss:

Oh no. It was always that way. I don’t know, can you really change your handwriting?

Debbie Millman:

It’s interesting. I look back at my handwriting when I was younger. It was much neater than it is now. Now I scribble more. But I’ve also noticed that my mother’s handwriting has never changed, ever. From the time I remember first seeing it till now.

Adam Moss:

I don’t think my handwriting has changed. My signature did after I spent a good deal of time trying to perfect it and make it look lovely.

Debbie Millman:

And why did you do that?

Adam Moss:

Because I’m vain and because I hoped one day that somebody would want my signature on something other than a check.

Debbie Millman:

Oh yeah, an autograph maybe.

Adam Moss:

Yes.

Debbie Millman:

You were born in Brooklyn.

Adam Moss:

That’s true.

Debbie Millman:

But your family moved to Hewlett, Long Island when you were a little boy, when you were a junior in high school. I understand you were a bit of a theater geek.

Adam Moss:

Oh my God. Where did you get that information? Yes, but actually it was earlier.

Debbie Millman:

Even earlier.

Adam Moss:

Yeah, it was my geek-itude. Theater geek-itude was exhausted by the time I was a junior, largely because I didn’t really have the aptitude that I had fantasized having as a younger person. I was actually a pretty good actor when I was 11, and then I hit puberty and it really just all just vanished.

Debbie Millman:

Were you more of a dramatic actor or a musical actor?

Adam Moss:

I aspired to be a musical actor. I aspired to be at chorus boy, that’s what I wanted more than anything.

Debbie Millman:

The reason I was mentioning junior high was because I understand that when you were in junior high every year in your school, a student got to direct the annual play and you wanted that job. You wanted-

Adam Moss:

You have such excellent researchers. Yes, that is true.

Debbie Millman:

Because of your experience at the time and your passion for theater, you thought there was no one else even remotely qualified to get the job of director of this play. I’m wondering if you can share what happened next.

Adam Moss:

I did look around and I was an actor. Also, I had been in the school play over and over, and I had done a million parts. I must have played every part in You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown in camp. I loved it. Yeah, I thought it was just my turn and it wasn’t. There was one day when they were supposed to tell you whether you… There were three finalists and I was one of the finalists, and I invited two of my friends to be with me when I got the big phone call, and they did a very cruel thing, which is that they made the person who did get the job call the person who didn’t get the job. So I got that phone call from this lovely girl who did a great job to tell me that I had failed to get this job, which was crushing.

Debbie Millman:

Oh, I can understand. I was also a theater geek in high school, and remember when I didn’t get parts that I so desperately wanted.

Adam Moss:

Yeah. But they gave me as a consolation prize, they were doing Fiddler on the Roof and they gave me, I was Motel that year. So that was fine. I got to sing Wonder of Wonder, Miracle of Miracles, and all was fine.

Debbie Millman:

I don’t know if you’re going to want to talk about this and we can always edit it out, but I understand that when you didn’t get the part-

Adam Moss:

Oh. My mother ran into the principal’s office. Is that what you want to talk about?

Debbie Millman:

Not so much that part.

Adam Moss:

It was an amazing thing because my mother did not have a history of standing up for me this way.

Debbie Millman:

That’s why I was going to ask you about it.

Adam Moss:

But she was horrified and moved, I think, by my terrible sorrow. Yeah, went to the principal and said, “Why didn’t he get this job?” Or whatever you want to call it, this assignment. And the principal said, “He’s not a leader. He does not have the ability to get other people to rally around something,” which I don’t know if it was true at the time, but it certainly in retrospect was a very helpful thing to me, even though it was cruel and crushing because it spurred me to be the person he didn’t think I was.

Debbie Millman:

You have written about how you thought that maybe it was the beginning of your real ambition.

Adam Moss:

Yeah. [inaudible 00:05:39] always had a ambivalent feeling about ambition. I think I was always ambitious. In fact, the signs of my ambition are very, very clear if I do a retrospective look at my life. But I came of age in the 60s and ambition a dirty word, even though ambition just really took different forms. But the notion of ambition was somehow tied to capitalism, even though that was not at all what I wanted, but I was afraid of wanting something too much. So I struggled with that as a way to identify myself, and then at some point I had to concede that I was a very ambitious person.

Debbie Millman:

I don’t want to go too far into the future, but I do want to ask you this question about when you left New York Magazine because you stated that your plan for the future was to try living with less ambition.

Adam Moss:

That’s true, and I think I have succeeded. It took a little while to get used to that, but ambition is exhausting. I had just had it as a habit for so long and I was kind of wiped out. I did try for the first months after I left the job to try to live a life of simpler pleasures, not needing the dopamine of the things that ambition gets you. I started to paint and I started to paint just for myself, which was a kind of ambition, but also not a public ambition. Then it really wasn’t until I wrote this book and even this book that I wrote, I wrote it for myself. I did not write it in order for it to be a bestseller or something. I wrote it to just satisfy a curiosity that I had and actually a kind of obsession that I had that was not an ambitious obsession. It was more of a personal obsession. So I think that I do live with less ambition now and I’m happier for it.

Debbie Millman:

Your book is very much a deconstruction of how people are artists and how people make art, and it occurred to me when I was thinking about the role of ambition in your life, the role of ambition in my life. I was wondering if there was any type of common denominator that you began to understand in the artists that you spoke with about the role ambition plays in their lives?

Adam Moss:

I think ambition is very important in an artist’s life, particularly an artist of the kind that I talked to for this book, this dataset of 43 of them, because ambition is one of the things that fuels drive and that you need a kind of superhuman drive to accomplish what these people have accomplished, but also the creative life is just full of obstacles. There are just bits of self-sabotage, landmines everywhere you step and in order to persevere through them, you need fuel. And that fuel can be a lot of things. It could be outrage, it could be sorrow, it could be loneliness, but it is often propelled by ambition. Now, that’s not mean necessarily ambition to sell a million dollar painting, although that comes into it. It’s the ambition to make something, but then we can talk later even about that because it’s really more the ambition to make rather than the ambition to make something.

Debbie Millman:

The one thing that you said about that experience that I thought was really compelling was you telling yourself, “Fuck this, I am strong enough. I can do this.” And it made me wonder if the very seed of ambition is about proving something to oneself.

Adam Moss:

I think that’s absolutely true. Even if it’s the kind of ambition that requires validation, the reason you require that validation is that there’s something that’s missing in you and that you’re trying to fill.

Debbie Millman:

Going back to some of your-

Adam Moss:

Long Island?

Debbie Millman:

Origin story. Yes. As you were growing up, you discovered what you’ve described as your own piece of library paradise in the stacks of magazines at your local library where you perused old periodicals from World War II. That really surprised me. You described these as stimulants for your imagination. What interested you in that particular time period?

Adam Moss:

It was really just the availability of it, but also the magazines of the 40s are wonderful and the advertisements of the 40s are wonderful, and I would spend as much time perusing those as I would reading stories. But I suppose if I was going to be in a shrinks chair, it was also my parents’ era, so I was interested in the life that they lived. It’s a kind of just way to live history, to rediscover history, but also I got very entranced with the magazine form, which was complemented by a kind of simultaneous worship of the magazines that came through the mail slot in my house, and that I would read at other people’s houses.

My parents were charter subscribers of New York Magazine, which opened up the world of New York City, which was enormously appealing, especially considering how uncomfortable I was in the suburban life that they had put me in. So this was a kind of a exit door, exit door of the imagination, but it was an exit door. And also magazines in like 1966, ’67, ’68, ’69, ’70, ’71 were fabulous laboratories of storytelling experimentation, in addition to being very exciting because the times were very exciting. So the dual action of visiting magazines of history and visiting magazines of the present or then present, just really excited me. I was just into magazines as early as I can remember.

Debbie Millman:

Was it just magazines or was it also newspapers? Long Island Newsday was quite good in the 70s.

Adam Moss:

Yeah, I wasn’t actually into newspapers. In fact, later I would get a job through strange circumstances as a copy boy at the New York Times, a job that any person who aspires to be a newspaper reporter or editor… Well, no one aspires to be an editor, but reporter would love, and I was blasé about it. It was interesting. I found it interesting, but it wasn’t actually what I wanted to do because I didn’t find the newspaper itself as a form to be as compelling to me as what was going on in the more subjective and visually enthralling world of magazines.

Debbie Millman:

You said that you got the job as a copy boy or a copy… Copy-

Adam Moss:

Copy boy, that’s what it was called, yeah.

Debbie Millman:

Under Strange Circumstances. And I’m wondering what those were because I couldn’t find out. I really searched for the way in which you entered the world of the New York Times. I know you went to Oberlin College, and I know you had an internship at The Village Voice, but I could not find out how you got to the New York Times.

Adam Moss:

Well, I’ll tell you.

Debbie Millman:

Okay. Yay.

Adam Moss:

I graduated from college. I had worked at The Village Voice the summer before. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life though I was, as I say, very excited about the prospect of journalism. No more magazine journalism, the newspaper journalism. And my father has a friend, still alive, who was dating a Swedish woman, and that Swedish woman was very interested in marrying my father’s friend. And that Swedish woman, having never met me, vouched for me to her friend, her other Swedish friend who happened to be married to Sydney Gruson, who was the vice chairman of the New York Times. And so without inviting this call, I got a call one day from Sydney Gruson’s office and said, “He would like to meet you and would you come up and see him?” So I did, and I got stoned before I went, but that was-

Debbie Millman:

As one did at that time.

Adam Moss:

As one did at that time. But that was the kind of level of it didn’t matter to me really. He had two children, one child who went to Oberlin, and the other child who went to Harvard, and I had had a short stint at Harvard as well. He was very interested in the establishment, non-establishment, duality of his children’s experience, but also of my own life. We got along great, and I walked out of there with a job.

Debbie Millman:

Did the Swedish woman marry your father’s friend?

Adam Moss:

She did not.

Debbie Millman:

Oh.

Adam Moss:

Sad story.

Debbie Millman:

Yes.

Adam Moss:

But anyway, I did meet her at one point and she was a lovely person. And I’m very grateful to her for that, even though it was a bit of a surprise, but I should probably say… Do you know what a copy boy was? It’s a great old vestigial job. It was back before computers, of course. A newspaper had editors and writers, and when the copy had to go from editor to writer, the writer or the editor would raise their hand and yell, “Copy,” and you would run and grab the piece of paper and run to the other, the reporter or the editor, and run back and run back and run back and run back. It was a crazy fun job that just vanished like so many others.

Debbie Millman:

Yeah, it sounds like the ball boy or girl at a tennis.

Adam Moss:

Yeah. It’s similar. It’s similar, yeah. But during this time… So I worked there at night and I worked at Rolling Stone during the daytime because that was a magazine and they were starting a new magazine for college students. So I really, I had a life of working one job, then working another job and never sleeping and was wonderful time.

Debbie Millman:

You worked at Rolling Stone putting together a magazine called The Rolling Stone College Papers, and then from there I believe you were simultaneously at the New York Times, but then went on to Esquire–

Adam Moss:

That’s correct.

Debbie Millman:

To work on their annual college publication. But that magazine was killed the day after you arrived at Esquire?

Adam Moss:

I believe it was the day I arrived.

Debbie Millman:

Oh, the day of.

Adam Moss:

But in any case, it was too late. They had me. They had hired me as a pipsqueak editor, and it was a wonderful time to be at Esquire because Philip Moffitt and Chris Whittle, who had bought the place were somewhat insecure about their abilities to edit a big city magazine. They had come from Tennessee having done a very successful startup thing there, which gave them the money to buy Esquire. And they had brought back the great editors. One of, I talked about the New York Magazine, but one of the other, of course fantastic magazines of the 60s was Esquire, probably the best run of a magazine ever. That was really my dream job. So there I was, and they had brought back all these editors and the editors weren’t much interested in working, and they were very happy to have a young editor to do their jobs for them.

Debbie Millman:

So before you were 30 years old, you worked for The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, the New York Times, and Esquire?

Adam Moss:

That’s true.

Debbie Millman:

What did you make of that trajectory?

Adam Moss:

I didn’t think about it. The only thing I realized was that I was the only one of my college friends working, and because you just didn’t do it in those days. You would go through Europe with a backpack or-

Debbie Millman:

Peace Corps.

Adam Moss:

Yeah, Peace Corps and work on a farm. And I had a very unusual career trajectory. And it never felt like it was any decision I made. It was just the way things happen. Of course, in retrospect, you see all the decisions you actually did make to make it happen, but it was not how I experienced it.

Debbie Millman:

In 1987, Leonard Stern, the owner of The Village Voice, was looking to start another and invited you among many others to pitch ideas. I read that Leonard didn’t have a strong sense of what he wanted to publish other than he wanted to create a magazine that was, in his words, less pinko. Allison Stern, Leonard Stern’s wife, was particularly interested in what you pitched, although it seemed when you were pitching that Leonard was not as interested. Can you talk about what you pitched and how you developed the original idea for the pitch?

Adam Moss:

At Esquire, I had been working on this other magazine, I think it was called Manhattan. It was-

Debbie Millman:

Manhattan. Yeah, Jay [inaudible 00:18:26].

Adam Moss:

It was nothing.

Debbie Millman:

I just have to interrupt you for a second.

Adam Moss:

Yeah.

Debbie Millman:

It wasn’t nothing at the time.

Adam Moss:

Where it went was something, but my pitch, you asked me what my pitch was. My pitch was like… It was really… I thought there was a place in the market between The Village Voice and New York Magazine, and I had this half-assed idea of what that could be. And I had presented it to a consultant, a guy named Jack Berkowitz, great guy. And he told me my idea was terrible and that it would never make any money because he was looking at it from that perspective. But he was also the consultant on this project, and he had said to me, “Hey, just pitch it. They’re having a bake-off. Just pitch your idea.” And I pitched, and I really don’t think the idea had much merit at all. But I think my own eagerness was probably winning.

And yeah, it was 10 o’clock at night in skyscraper, in 50s I think, in Manhattan, and I pitched the thing, and there was utter silence. Allison had just injured the room. I think mine was the only idea that she’d heard, and I think she thought the whole thing seemed fun. Really out of shame because the silence was so awful, I went to the bathroom. This is the story you’re looking for, I’m sure. At the urinal, I was doing my business and Leonard came in to do his business and he said, “Yeah, we’ll do your magazine.”

And then I got a bunch of people together and hired, well, I think a bunch of children, which was all I could afford, and thank God for it because there was just a kind of youthful passion and somewhat organically Seven Days emerged, which was basically a function of our own naivete about what a magazine should feel like and look like. But it became this kind of conversational collage that reflected the week. It was different and probably fresh. We got a lot of incredible talent work for it. Yeah, it was all wonderful.

Debbie Millman:

It was a wonderful sliver of time in the world of magazines at that time.

Adam Moss:

You have to remember that that was a period when there was a lot of optimism [inaudible 00:21:03] magazines and there were starting up all over the place.

Debbie Millman:

Yeah. New York Woman, Egg-

Adam Moss:

Spy.

Debbie Millman:

Spy, of course. I remember very vividly Seven Days, and not just Seven Days, but also this sense that Adam Moss had arrived. And he was now-

Adam Moss:

Oh, You’re nice.

Debbie Millman:

No, no. I don’t want to fawn. That’s not what I want to do. But because it was such an important moment in my life as well. Living in New York surrounded by magazines, I was working at a number of different magazines. Nowhere as near in the stratosphere is the ones that you were working on, but it was still a great, great passion. I had a friend that worked at Manhattan, inc. and a friend that worked at New York Woman and a friend that worked at Spy. So I was very immersed in this world. And for our listeners, when Seven Days came out, it really did change quite a lot of the way in which you thought about and considered a magazine. And it’s interesting you said that you think the entire history of Seven Days is the history of people who didn’t know any better doing all the things that their elders had dismissed, because most of the time it didn’t work. But it did work for a while.

Adam Moss:

I still believe that.

Debbie Millman:

I still that it did work for a while.

Adam Moss:

Yeah, and it worked. It was a kind of accidental explosion of naiveté that yes, somehow worked. And prefigured a lot of storytelling forms that would emerge later around the internet in particular. But that kind of conversational, very subjective, personal expression, filter of experience of news experience, but also personal experience that was related to exactly that moment in time, that was what animated the magazine. And yeah, I look back on it, some parts of it I cringe at, but for the most part I’m just as excited. But it’s very much of its time so that somebody might chance upon it in a library, just the way I did those magazines of the 40s. And they will instantly know what the world was like in 1989 in New York City for a certain demographic.

Debbie Millman:

Despite only lasting two years. Two weeks after the magazine closed, Seven Days won the National Magazine Award for General Excellence, which is a highly competitive accolade. And this propelled you to begin working at the New York Times where you were brought in to quote, “Decalcify the place,” unquote. And you’ve said that in doing so at the time, you got a lot of grief. They didn’t want to be decalcified?

Adam Moss:

No, they certainly did not want. The rank and file did not. The rank and file, they were very invested in the establishment traditions of the New York Times. That’s why they worked there, and they were very important. But there were some leaders of the Times, Joe Lelyveld, the man who hired me in particular, who thought it needed some breaking down. Not entirely, didn’t want to change it. Tremendous reverence for the institution, but felt that it had some cobwebs. And so he assigned me this absolutely preposterous assignment, which is to go in there and make trouble. I was 30, and I learned very quickly to ignore my brief. Anyone who wanted to bend the place a little bit, I was there to help them do that. And there were some interesting projects. They were all pretty small.

But the one piece of the institution that I wanted to participate in, because it’s the only one that I had an idea about was the magazine. And the editor at the time was not interested in my being there for excellent reason. And eventually there was, this guy named Jack Rosenthal, and he asked me to come on first in this wrecker role, and then eventually as his partner, editorial director, and then I became editor of the magazine afterwards.

Debbie Millman:

How did you feel as a wrecker? Did you feel courageous at the time? Were you tentative nervous, ballsy?

Adam Moss:

Foolhardy. Naive. Naiveté is really, it’s a theme in my life. I think it maybe still is. I just didn’t realize how many traditions I was trampling on. But on the other hand, I also knew what I didn’t know. I was not particularly cocky. I was more like a child in a room of adults, and I acted like a child, and I played as a child, and that had benefits and that had a lot of problems. But I grew up fast there and they taught me a lot. And in fact, I feel very much formed by what I learned at the New York Times and very grateful for that education. I really became a journalist there. And before that, I was faking it.

Debbie Millman:

The magazine still has a lot of your imprint in it now, all these years later. It’s still very much influenced by how you reimagined it. Could be. It’s a magazine, it’s not an insert.

Adam Moss:

Yeah, I’d like to take full credit for that. But that was really… Like many of these things, that was really a confluence of a lot of things happening at once, largely economics. The Times was really making a national push into national distribution, but also a business model of national advertising. A lot of that advertising was magazine-like advertising. So there was a desire for the magazine to be a gatherer of that kind of advertising. And so there was a kind of… I don’t want to call it an open check because it really was not that large, but there was permission given to detach it from its history as a supplement and to turn it into a freestanding magazine that happened to be distributed in the New York Times and that had the New York Times DNA, which was a really interesting brief, and one that Jack and I worked on. And then later I worked on with the staff as the editor.

Debbie Millman:

You left the Times in the early aughts, but not after more accolades awards and increase in readership, a whole different way of really assessing the magazine. And you went on to New York Magazine as editor, and you were brought in again to remake it by then, owner Bruce Wasserstein. I read that you approached it as a kind of restoration project as opposed to a re-imagination, and you wanted to bring back some of the values of the original co-founders, Clay Felker and Milton Glaser while still pointing it to the future. What were the values you deemed most important to restore?

Adam Moss:

One of them was both Clay and Milton had a perspective that what the magazine was really about was not New York City, but a New York City way of looking at the world. And that there was a filter that could be applied to Washington, could be applied to Hollywood, could be applied overseas to London, other places, that it was really a magazine of the cosmopolitan world. New York Magazine inspired a lot of city magazines, but it actually never was a city magazine. And the owners of the magazine before Bruce took it over, very much remade it themselves in the mold of the magazines that were imitators of New York. So I was trying to go back to that original idea, which I thought was bigger and more interesting and more adventurous, and to remake the magazine in 2004 to feel like it was a magazine of 2004, but it had the values that animated its founding.

Debbie Millman:

Adam, we could do a whole series, a whole series on Design Matters about the relaunch of New York Magazine. But I do want to get to your glorious new book. Suffice it to say that since the redesign and relaunch in 2004, New York Magazine has won more national magazine awards than any other publication, including the award for General Excellence in 2006, ‘7, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2016, as well as the Society of Publication Designers Award for 2013 Magazine of the Year. Most recently, the magazine won a George Polk Award in Magazine Reporting for the Bill Cosby rape investigation. And it’s also been awarded several Pulitzer prizes.

Adam Moss:

Many after I left, I just should say.

Debbie Millman:

Okay, but still-

Adam Moss:

But yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. Thank you.

Debbie Millman:

So congratulations.

Adam Moss:

Thank you.

Debbie Millman:

You not only re-imagined the print magazine, you also embraced the magazine killer called the internet and knew digital-only brands, five of which Vulture, the Cut, Intelligencer, The Strategist, and Grub Street are now considered heavyweights in modern online editorial. And New York Magazine is now as much of a digital company as it is a print company.

Adam Moss:

Absolutely. Yeah.

Debbie Millman:

When so many editors couldn’t or wouldn’t adapt their publications to the digital world, what gave you the sense that this was going to be the game changer it ended up becoming?

Adam Moss:

It wasn’t that I thought it was a game changer, it was that I thought that it was interesting. And I had come from the New York Times just recently, which had… They were making a few mistakes, but basically they were getting it right about how to create a digital newspaper. And I found that very exciting. And there were several experiments, even at the very early NewYorkTimes.com that I did with the magazine that were exciting to me. I wanted to bring that spirit. I just wasn’t scared of it.

And also, the owners of New York Magazine were not scared of the internet for reasons that really, I’ve told this story too many times and it’s boring, but they were making money on their own digital site for arcane reasons, but they were. That became a business imperative too. I just keep saying this, not because I’m an economist, but you need the right conditions on the ground to do anything creative really. And in all these instances, the right conditions, the right economic conditions enabled the creative things that we were able to do.

But I was just crazy interested in it, and each experiment we did trying to build out a sort of satellite, not a satellite, but a constellation really of digital magazines, was interesting to me and interesting to my colleagues. It spurred us on to do more and more and more. We started with this thing called Grub Street, and then… [inaudible 00:31:54] food. And then we realized, “Okay, if these things were vertical as opposed to horizontal,” which is to say about one subject, “That could be wonderful. And maybe the voice should be the same voice as the print magazine, but sped up for digital purposes.”

And gave a lot of license to the early writers who helped create the voice. Grub Street became Intelligencer, which eventually became Vulture, on culture and entertainment. And Intelligencer went through several iterations, but eventually became a news site. And then The Cut, which was a kind of women’s magazine, but a very different kind of women’s magazine than it had ever been made before. And lo and behold, we had this fleet of magazines that were built for the internet and had the DNA of New York in them. And that proved to really work.

Debbie Millman:

In 2019 after 15 years of nonstop growth and innovation, you decided to leave New York Magazine. At that point, you had also somewhat secretly taken to painting. Did your new fine arts pursuit influence your departure?

Adam Moss:

No, I don’t think so. I had always loved the visual parts of magazine making, and I have a house in Cape Cod that used to be an art school just by coincidence. And there is just a feeling of being there that you can see the ladies with their bonnets painting en plein air on the dune. And I found that interesting. And then one summer I just decided to try to do a painting a day without any… I had no experience, I mean like zero experience doing this, and I just started to experiment, started painting at three and ended at five, whatever it was it was. And that was crazy fun to me. And then when I got back to New York, someone made a gift of giving me an art teacher, and that was the first time I got a teacher, but I was still working in New York at the time, and…

No, I left New York because I felt that I could only edit the magazine for myself and that I was no longer the reader. I had seen the ways in which an editor who didn’t have themselves as a compass could screw up a magazine and how it could become contagious. I just didn’t want to do that, so I had to get out of the way. So I left without any sense of what I’d want to do, except as you’ve mentioned before, to try to do something with less ambition. It was more like, “Okay, let’s see what happens” without any true sense.

But I did enjoy painting enough that I thought, “Maybe I should paint full time. And I had a problem, which is that I actually was kind of good at the beginning. My first six months, I would say painting, I was a much more successful painter than I ever was again.

Debbie Millman:

Why?

Adam Moss:

Because I was looser, because I was naive. I didn’t know better. Really, it’s really, I can’t believe how thematically consistent this all is. And then as soon as I did know more, as soon as I took more classes and that kind of thing, my work started to just stiffen up and fall off a cliff. So that was deeply, deeply upsetting to me, and though I enjoyed it, it scared me.

Debbie Millman:

Why?

Adam Moss:

Because I really wanted it and I didn’t know how to get there, and I didn’t have any roadmap whatsoever to get there. I could acquire skills, but I was already, I think, aware that skills training wasn’t the problem. I did lack skills, but you can always get skills. I really felt that there was a way of thinking as an artist and a degree of courage and risk-taking that I did not have in solo activity. I’d had it in a group because the group is safe, and the group eggs you on and making something together in a group is really still the greatest thing in the world to me. But here I was alone and not making enough progress.

So that’s really when I realized that I just wanted to talk to people who were successful in making art. By art, I mean any kind of art. Novels and poems and visual art. And then I was afraid that they wouldn’t be truthful with me. They wouldn’t know how to be truthful with me because so much of the process of making art is secretive and people are afraid of jinxing the muse. So they develop a kind of set spiel, and that’s how they talk about their art, and it’s about the project and all of that stuff, but that’s not what I wanted to know. I really wanted to know how something is made and what goes through a person’s mind when they’re making it, and what goes through a person’s emotional makeup, what kind of person is successful at this?

So that’s when I devised this idea of concentrating on a single work from each of these people and asking them to trace the evolution in as many different layers as they could, both practically what they did, but also very much their kind of emotional journey. And then also part as a go to help them remember truthfully, and also just because I love this stuff, to accompany it with a gallery of the artifacts of the making of the thing, the notes and the sketches and the doodles that were their tools making the work. Then I looked at all that and I kind of had a book, or I had a structure of a book, or I knew what the book was.

Debbie Millman:

Before we talk about the book, I want to ask you another question about your own journey as a painter. Was it hard for you to suddenly not be good at something when you’d been so good at so many things for so long?

Adam Moss:

I think so. I had actually taken up piano earlier in my life, and in part because you have to listen to yourself play the piano, and I was really a bad piano player. I gave that up, and my thinking at the time was that I couldn’t tolerate not being good at something. It was just too painful to me. And I realized how many things over my life I had discarded that I wasn’t good at. I’m not good at most things. And because I’d had this one moment when I thought, “I maybe could paint,” it wasn’t the same thing. It wasn’t something I was just going to throw over.

And also because I really physically enjoyed making art, I enjoyed the physical sensation of it in a way that was new to me and was exciting to me. And so I didn’t want to give it up, but I think it was more vexing to me because in a kind of group… There’s a chapter in the book on David Simon where somebody observes that he needed the bounce, this great phrase, the bounce to make television, to make the wire, which is what we were talking about. And I recognized in that that was really how I had worked my whole life, is that I had thrived in the bounce. The ricochet between creative people was really… That was the environment in which I was successful, and here I was just by myself, and it was an environment that I was not being successful, and I was trying to capture the inner dialogue. I knew what the group dialogue sounded like, and here I was trying to capture the inner one.

Debbie Millman:

So the struggles to understand your own voice as an artist is what led you to… That was a driving force behind-

Adam Moss:

Yeah. My voice, how you endure through failure and frustration, a very, very big part of it. How you… Some simple things, really actually not at all simple things, but simple to describe, where to start, where to end. What gives you the faith that you can do this. These were all questions that were questions of temperament and personality. And so in some ways, I don’t really usually describe it this way, but I was trying to understand the artistic personality.

Debbie Millman:

One of the things that first attracted me to this effort was the title, the Work of Art, which I think is one of the great book titles of all time, I have to say. This subtitle is How Something Comes from Nothing. But is it true that the original title of the book was Editing?

Adam Moss:

Yeah. Well, originally-

Debbie Millman:

It’s so different.

Adam Moss:

I know, it’s so different. Although the original idea of it was to try to claim for editing a much wider sense than we usually have for it. So I wanted to talk about editing as what I’m doing right now and choosing this word instead of that word or how we dress, or basically how we make artistic decisions, make decisions, and that was what the book was going to be, and it was going to be as applied to creative people and blah-blah-blah-blah-blah. Eventually that just became too limited because the editing, which is kind of this mid-zone, I think, between the imagining and the shaping, there’s a kind of judging aspect, which is similar to the function of editing. Editing just seemed too limited a term. But in some ways, the book is still about editing. It’s just not editing the way I think anybody thinks of what the word means.

Debbie Millman:

Yeah, in many ways, editing is about choice-making.

Adam Moss:

Absolutely.

Debbie Millman:

And this is a book about how you made choices to create this thing that you created.

Adam Moss:

Yeah, absolutely. That’s exactly true. Yeah.

Debbie Millman:

I read that you hate writing and that you think you’ve been a terrible writer for most of your life. How is that even remotely possible, Adam? I can’t even come up with the right kind of question to ask you about this.

Adam Moss:

Just think of it. If you’ve been an editor all your life, you have a very keen sensitivity to what is off, and that applies to your own work as well. I was super self-conscious, and I had this overly wound up editing scrutiny of my own work, and it got me nowhere. I had to really teach myself to write for the book, and that was a wonderful process actually. Although agonizing. I wrote the book really in a voice that was just completely not me. It was a voice that I just made up, is what I thought a book should sound like. It was really pretentious. And everything was an overreach. And then I-

Debbie Millman:

Did you decide that, or did an editor decide that?

Adam Moss:

No, I decided that it was just, I had this wrong-headed idea about what… “Okay, I’m an author now, how should I sound?” Terrible. A good enough editor recognized how bad it was, and then I went back and rewrote the whole book once I actually did find my voice. I think why I hated writing so much is because I just hated what I was writing.

Debbie Millman:

You wrote that you decided to create a book deliberately in a way that would be writer-proof.

Adam Moss:

Writer proof, yes.

Debbie Millman:

And that the writing would be the least important part.

Adam Moss:

Yes.

Debbie Millman:

But I don’t think that that is the result at all. I think that part of… Some of my favorite parts of the book are your musings and candor in looking at what you were looking at and coming to the decisions that you did. My favorite parts are the parts that you actually wrote,

Adam Moss:

And you know what? Those were all the parts that I added at the end. So at the beginning, it was very much the artist’s voices were the driving force of the book, and I had a conversation with a wonderful editor friend of mine named Susie [inaudible 00:43:57], I’ll give her a moment here. And she said, “Where are you in this book?” I had to reluctantly concede that she was right, and she had the idea that the footnotes were a particularly good way to impose myself on the book in a sort of Talmudic way. But I also rewrote into the book. At that point, the book opened up. It really became a different book and a much better one, I think.

Debbie Millman:

You were invited by Frank Rich, a writer from the New York Times and New York Magazine, and also an executive producer of the television program Veep to visit the show. And that became a real impetus for writing this book, and I’m wondering if you can talk about how that happened.

Adam Moss:

Sure. I went to the set of Veep and I sat with the writers who all sit in little director’s chairs behind David Mandel, who was the showrunner of the show at the time. And I watched them do a scene that probably didn’t last more than five minutes all afternoon or a good deal of the afternoon. And there was one joke in there that landed on a Jewish holiday, and Dave Mandel did not think it worked exactly. So he had summoned the group to come up with what are called alts, which was alternatives to the joke to calibrate the joke and fine-tune it and make it funnier. One after another that he just barked an alternative out. He changed, he just kept changing the holiday. It was like Hanukkah, and then it was like Purim and Simchat Torah.

Debbie Millman:

[inaudible 00:45:32].

Adam Moss:

Simchat Torah because it’s the funniest. And Purim. And the group would laugh or they wouldn’t laugh. And finally he came up with the thing that he liked best. I can’t even remember what that was. He can’t even remember what that was. And I left just in awe of the kind of rigor that they brought to a joke that would be an absolute throwaway moment in a television show that nobody would notice. It was just like it’s wallpaper. I love that. I’ve always been a Calvinist. I’ve always been an admirer of work, and I’ve always really been an admirer of creative work. I walked out of there. It wasn’t at that moment that I decided to do the book, but it was one of the seeds that spurred the book on.

Debbie Millman:

One of the things that I like so much about the book is how the process, so to speak, and I hate the word process-

Adam Moss:

Me too.

Debbie Millman:

But the magic of creating art is revealed, and so many times, because great works of art, whether they be great jokes or great puzzles or great sandcastles or great paintings or poems feel effortless. It takes so much work to get to that loose.

Adam Moss:

Absolutely. Effortless. So much effort to make the effortless, yes.

Debbie Millman:

Yeah. And that example of trying out the different jokes… I also learned a lot. I had no idea that that’s how jokes-

Adam Moss:

Yeah, me neither.

Debbie Millman:

Can be constructed, that you try all these things out. It just seems like they’re so effortless that they’re just fully formed. And that’s not the case in the 43 case studies in this book. Just to give our listeners a sense of this opus, it features interviews, sketches, scripts, drawings, drafted pages in journals, song lyrics, story outlines, and all sorts of intriguing never-seen-before ideas in the making of some of the most preeminent artists of our time. They span genres and mediums. They include filmmakers, songwriters, painters, playwrights, composers, poets, chefs, a puzzle maker, a sandcastle maker, a cartoonist, a newspaper editor and designer, and even a radio pioneer. And you interview more than 40 people. You ask them to take you through the process of making one specific work and drawing on what you call process artifacts to chronicle their thinking. How much fun was this project?

Adam Moss:

Enormous fun. Two parts of it were really fun. The first part of it was the conversations with the artists themselves. I loved that. I am intrinsically a worshiper of creative people. I just really admire it. And so that I just love that and I learned so much. And then I also loved the physical construction of the book. I worked with-

Debbie Millman:

Like Hayman.

Adam Moss:

Luke Hayman and his colleagues at Pentagram, and he was very generous in letting me play with him and his colleagues to make a book that we both wanted to be a book that didn’t look or feel like other books. So I really enjoyed that part too. Now, we had talked earlier about the part that I didn’t like, which was sitting in a room and writing the damned book. I just found that to be agony.

Debbie Millman:

You write about Elizabeth Gilbert and how in her TED talk on the subject, Elizabeth Gilbert speaks about how in Ancient Greece and Rome people believed that creativity was this divine attendant spirit that came to human beings from some distant and unknowable source for distant and unknowable reasons. And it reminds me of something Rick Rubin wrote in his book, The Creative Act. He stated that, “If you have an idea you’re excited about and you don’t bring it to life, it’s not uncommon for the idea to find its voice through another maker.” And this isn’t because the other artists stole your idea, but because the idea’s time has come. And I’m wondering, speaking to so many people about the way in which they approach their work, do you feel that that muse is sort of out there for an artist through hard work and sitting in the chair every day will come to them, or is it something that they conjure? I really struggle with the idea about whether ideas come through the artist or from the artist.

Adam Moss:

It’s got to be both, don’t you think? That’s when it really works, is that if the artist brings what they have inside them to the table, or those that feel that it’s otherworldly, if they’re struck at that moment by some otherworldly inspiration. It must meet the moment. There’s really many, many instances in this book of work that I don’t think could have been made if it had been made at a different time. That’s true of historical circumstances or economic circumstances. But it’s also true of just the artist’s experience. The artist gets to a point where he or she can make the thing. And before that, it would’ve been impossible. Or a medium has changed. I mentioned David Simon. David Simon could not have made The Wire if HBO hadn’t existed. So there are all sorts of things that create opportunities and the opportunity meets the internal churning of the artist, and that’s when the greatness happens.

Debbie Millman:

You mentioned earlier in our conversation that artists can sometimes be secretive about their process, and I’m wondering, is it really being secretive or is it being unaware and not necessarily being able to admit that?

Adam Moss:

I think both. I think that’s very true what you say. A lot of them are secretive, A lot of them are superstitious. There’s a tremendous amount of superstition involved with this because people fear that it’s fragile. Whatever their connection is to however they identify the muse, it’s tenuous and easily broken. And if they look at it too hard, the whole thing will just dissolve in front of them. So it took a certain kind of brave person or a foolhardy person, or just a really introspective kind of person to want to participate in this project. And there were a lot of people who said no, and it was a sorting of the sort of like, “This sounds interesting to me,” because to your point, I never think of this before, and now you’ve just made me interested in where these ideas come from. Tony Kushner, who’s a very introspective person, said, “As I’m writing something, if something good comes out, it’s like, where did that come from?” It is a question that they don’t necessarily know the answer to. So a lot of these artists felt that our conversations were akin to therapy.

Debbie Millman:

You write that in your view, there are three stages of making art. The first is imagining, and the final one is shaping, which are somewhat self-explanatory, but the one in the middle and the one most interesting to me is judging. Can you talk a little bit about what that is?

Adam Moss:

We’ve talked a lot about judging in this conversation, so that the judging is what someone else might call editing, it’s bringing intelligence to bear on part one, which is what has the imagination brought, which generally is a kind of big mess that happens if you think of a first draft of a story or you think of a first pass of a painting. It’s kind of just a this and that kind of jumble, but under there, somewhere there is something worth working on. And it’s not the latter part, the shaping, that’s as you said self-explanatory, I think that’s true, which is the technique, the whittling, et cetera. It’s really, what is this and what could it be? It’s more of a thinking process. It’s the engagement of the brain. It’s not necessarily a conscious engagement of the brain, but it is something that the brain is doing to try to make sense of what they have in front of them and what it might turn into.

Debbie Millman:

As I was thinking about this, it felt like this was the manifestation of an idea, and that to me seemed like the most interesting part of the work. The imagination part, you get the spark, you don’t. You get the idea, you don’t. But the making part is the most fun.

Adam Moss:

I think so. I think it’s the most important stage, and it’s a stage that no one gives a whole lot of thought to. Technique is fun and there’s all sorts of wonderful pleasures in making anything physically. But the really crucial moment is the evaluation and the strategy, which is what this middle part is about.

Debbie Millman:

Many artists in the book also talk about getting into a flow state, which I often compare to an athlete getting in the zone. That period you describe as one of utter absorption where all the distractions in life disappear. Time even seems to evaporate. Did any of the artists in the book have tips for igniting or expediting or extending that state?

Adam Moss:

No, unfortunately they did not, but they all, almost to a one, talked about it in terms of exaltation. It’s the reward. I thought of it very much akin to almost a hallucinogenic experience, and it has that same kind of body high to be in it.

Debbie Millman:

Yeah, it’s magic. At the beginning of the Art of Work, you state that you’re a painter, but you feel ridiculous saying that.

Adam Moss:

Yeah.

Debbie Millman:

You feel ridiculous saying that. After all these interviews and this deep examination of what it means to be an artist, do you still feel ridiculous?

Adam Moss:

I still don’t know that I would call myself a painter. I don’t feel ridiculous painting. There’s something that actually I heard on your podcast that was really very helpful to me, and it was Lynda Barry was on. And she talked about how nobody, when they get on a bicycle… Do you remember this? How nobody when they get on a bicycle thinks that they can win the Tour de France. They ride a bicycle because A, they’re trying to get somewhere, or B, they’re just trying to have a good time. And why do we think differently about art?

There was something at the end of this project about people’s insistence that the piece, the work, the physical object that they were making, whether it’s a book or a poem or a painting or joke, was not actually the most important thing to them. In fact, they were largely indifferent to it. They were proud of it. It was good. It was nice. It was the end. They weren’t dismissive of it typically, although sometimes they were. But they did feel that it was not the point. That the point was the, what I like to think of as the verb, was the making.

And once I got that, I had a different attitude about my painting. That sense of critical punishment I was inflicting on myself disappeared, and I felt the pleasures… Whether they were flow state pleasures or not, I felt the pleasures of the making, and that gave me delight. And now I actually really do love painting. I know it sounds pat, but it is true that it gave me back my love of painting. I’m painting obsessively again, but I’m not painting obsessively to make good stuff. It’d be nice if good stuff happened. I have no problem with that, and I am getting a little closer to maybe showing my painting-

Debbie Millman:

That was my next question. I know that the only two people that have… Well, I think… Did you show it to one interviewer?

Adam Moss:

Yeah. I let Ari Shapiro from NPR. He wanted a scene, and I understood that as a magazine editor. And I thought, “It’s radio. I can let you into this room and no one will ever see what you saw. So okay, you’ll see it. And you’re lovely, generous guy. And I’m sure you’ll think it was fine. But the audience won’t see it.” So I did let him in, yes.

Debbie Millman:

So he’s one of three. Your husband, your art teacher, and now-

Adam Moss:

Although someone else reminded me that they’re number four, because it’s someone that I had been sharing the studio with for a while and I kind of forgot that he worked within. When I wasn’t there, he worked within the world of my work.

Debbie Millman:

Well, I hope the world gets to see it at some point. My last question isn’t really a question. It’s really more of a quote. I want to quote something that you said. You were asked about finishing the book and being out in the world, and if you have a better understanding of the mystery of making art, and you said this, “I’ve gotten one part of the answer, which is that the work of art is the work. It’s the most banal observation, but that it’s not about the thing you make, it’s about the making. It took me three years to figure out that that was actually true.” And let me tell you, it has changed my life.

Adam Moss:

Yeah.

Debbie Millman:

Adam, I just want to say thank you. Thank you for making so much work that has mattered for so much of my life, my adult life, and thank you so much for joining me today on Design Matters.

Adam Moss:

Oh, thank you, Debbie. I’ve really enjoyed this conversation. Thank you so much.

Debbie Millman:

Adam Moss’s latest book is titled The Work of Art: How Something Comes From Nothing. This is the 19th year we’ve been podcasting Design Matters, and I’d like to thank you for listening. And remember, we can talk about making a difference, we can make a difference or we can do both. I’m Debbie Millman, and I look forward to talking with you again soon.