We can seek out adult and children’s books in bookstores and libraries dedicated to important people in history. We can read magazine articles and click on Google Doodles, shedding light on folks who have been historically under-highlighted. We’ll undoubtedly find more stories about Black and brown people now, but there’s always more work to do in who we learn about and what we learn about their stories.

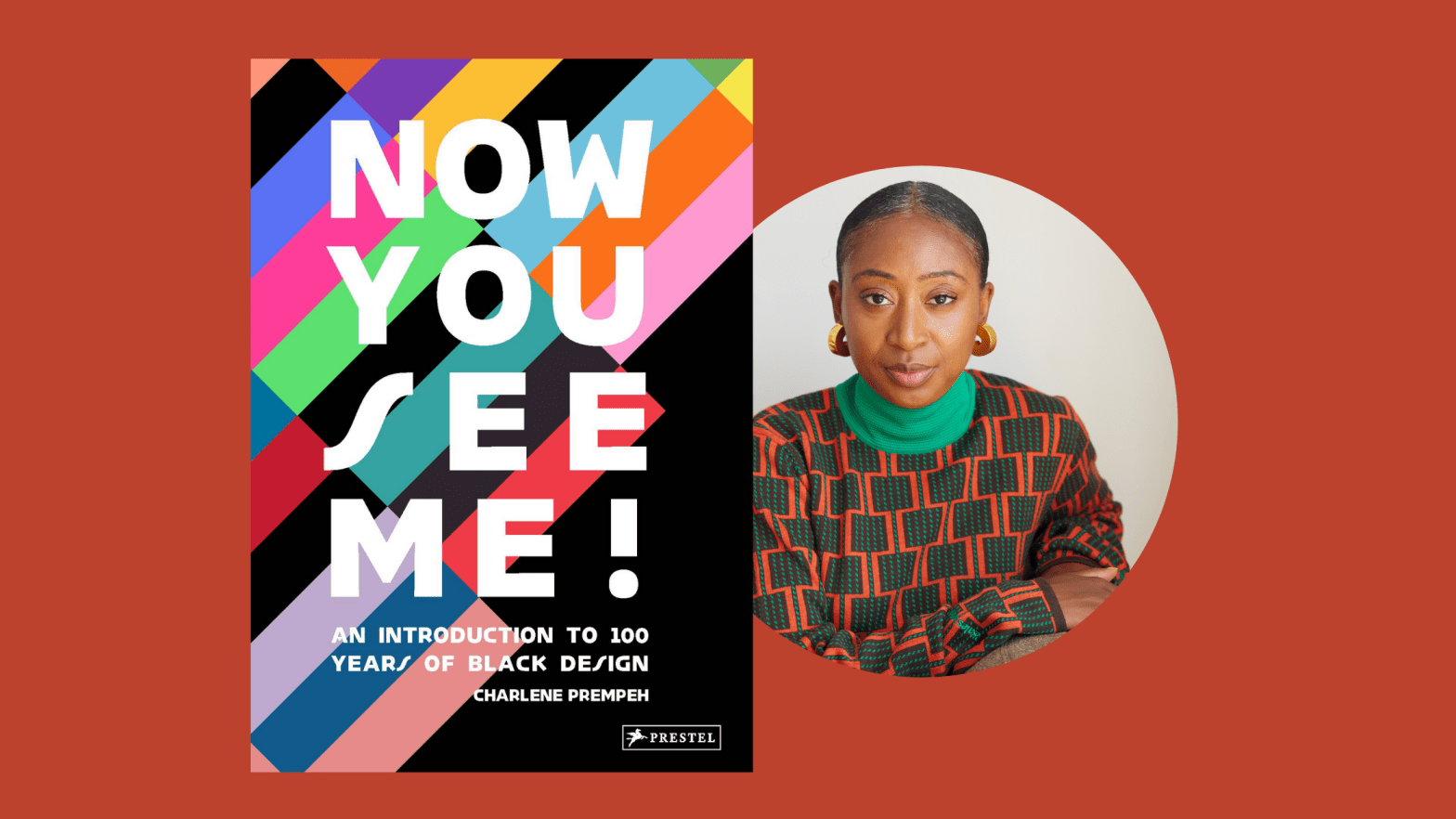

For Charlene Prempeh, author of Now You See Me! An Introduction to 100 Years of Black Design, it became clear that Black creatives weren’t getting their due. Her book researches the contributions of Black thinkers and creatives across the fashion, architecture, and graphic design industries—hoping to open up a more nuanced and layered conversation about them rather than the typically quick mention in Black History Month lists.

The book covers a century’s worth of creative innovation, and for Prempeh, every single story came with an “a-ha moment.” Not only did she learn about people she hadn’t heard of before, but she also revisited the prevailing narratives about familiar names.

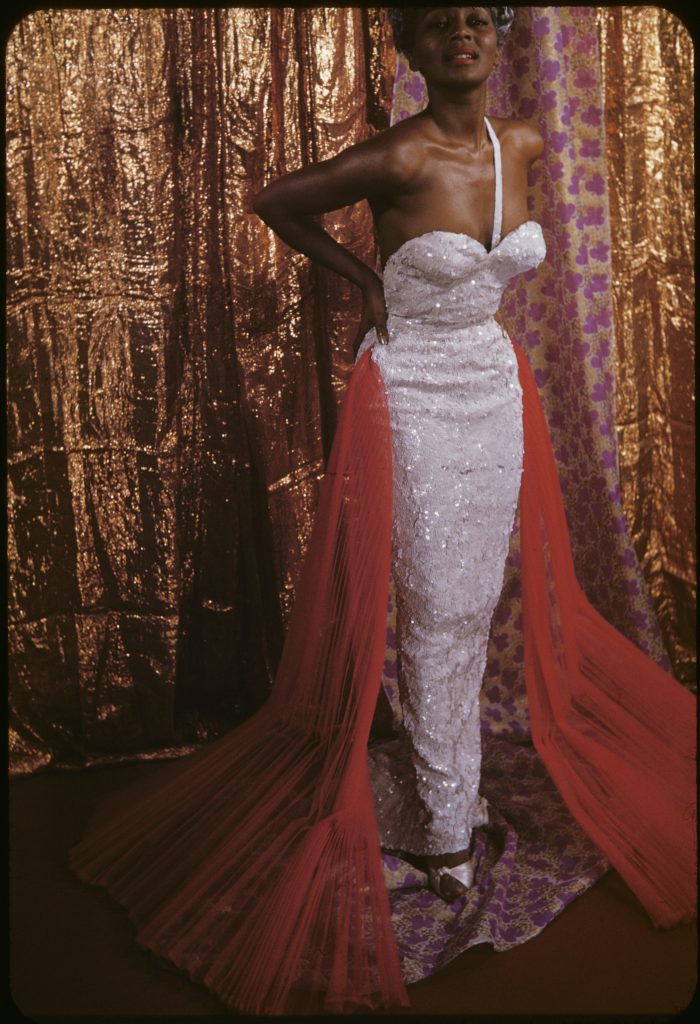

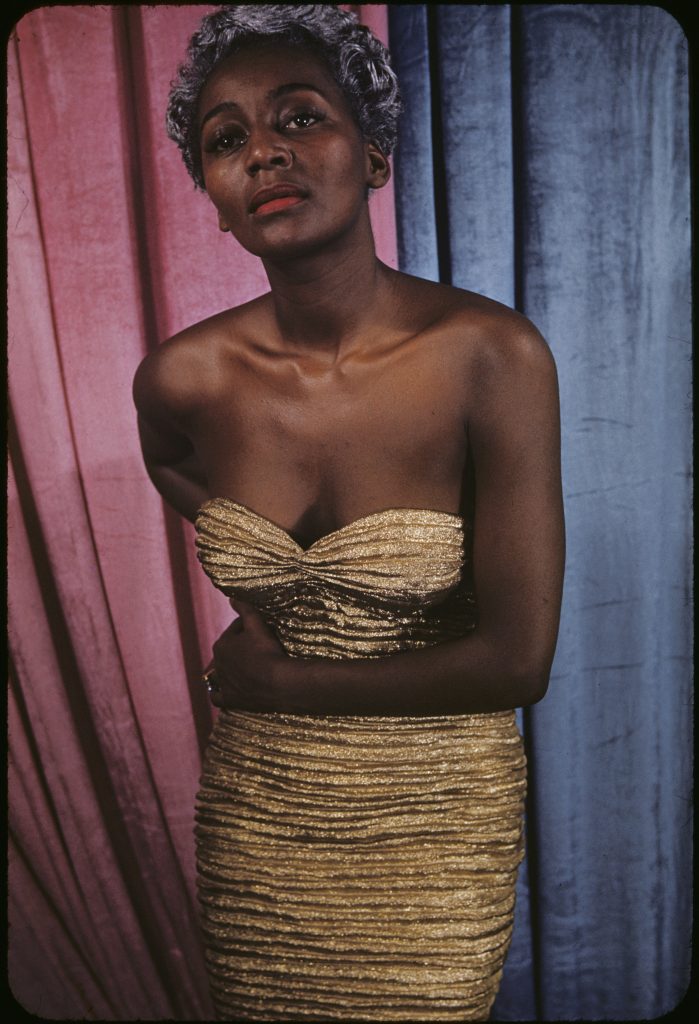

“What I thought I knew about them wasn’t necessarily right, or did not have the depth required to understand their journeys or practices properly,” said Prempeh. She gives the example of Zelda Wynn Valdes, who often gets mistakenly credited with designing the Playboy bunny costume. In her research, Prempeh found Valdes sewed the costumes rather than designing them; that experience points to “how surface our information is about these individuals.” In 2019, The New York Times published Valdes’ obituary as part of the “Overlooked” project, which featured “remarkable Black men and women” that “never received obituaries in The New York Times — until now.” Valdes passed away in 2001.

Left: Joyce Bryant in a figure-hugging gown by Zelda Wynn Valdes, 1953; Right: Joyce Bryant wearing one of the “tight-tight” gowns designed for her by Zelda Wynn Valdes, 1953 – Images © Van Vechten Trust

Now You See Me incorporates significant materials that help tell each person’s story, such as a letter by Ann Lowe to First Lady Jackie Kennedy, whose wedding dress she designed. Lowe read an article featuring Mrs. Kennedy in the Ladies Home Journal, which referred to her as a “colored woman dressmaker,” diminishing her identity as a designer. While many texts about Lowe’s life focus on her connection to Mrs. Kennedy, Prempeh sees her story differently. Lowe was “this woman who was brave enough to stand up for herself in a moment where it would have been much easier just to cower.”

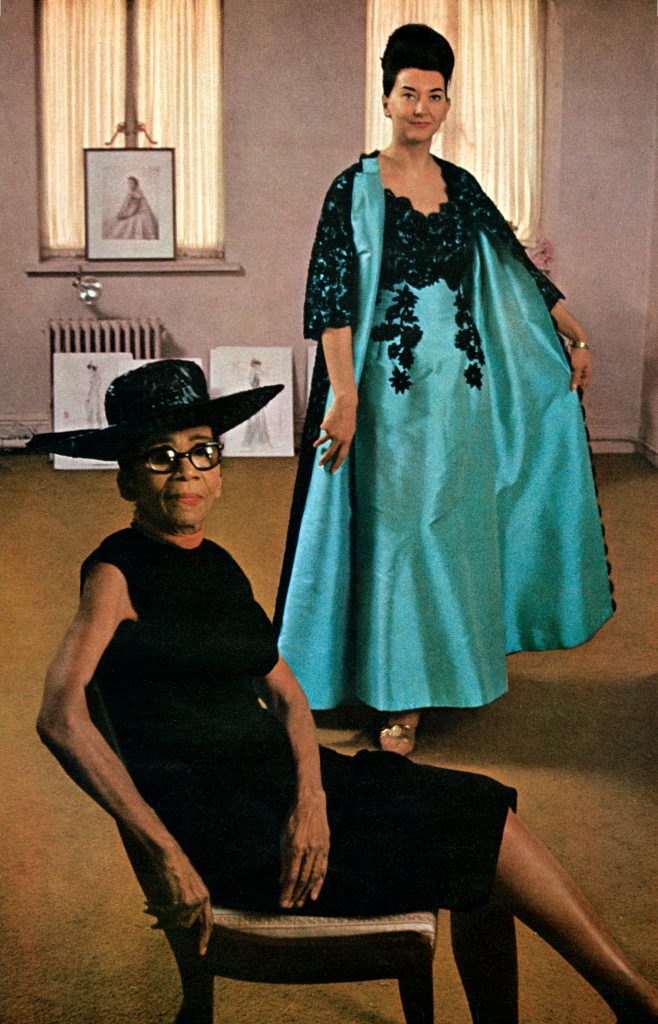

Left: Ann Lowe with the “First Lady” doll from the Evyan Collection, 1966; Center: Ann Lowe, Ebony Magazine, 1966; Right: Ann Lowe fitting a dress to a mannequin, 1966 – © Johnson Publishing Company Archive. Courtesy J.Paul Getty Trust & Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

“As a Black woman, or as a woman [in general], knowing that someone else did that at that moment in history gives me a sense that I can do that, too,” said Prempeh. “That if something is not right, [I can] stand up and say so.”

Yet, Prempeh emphasizes that writing about these makers means including their shortcomings as well.

“We sometimes struggle to be critical where it’s actually completely fair to be critical and where there’s an important lesson to learn in that criticism,” said Prempeh.

Now You See Me also weaves in Prempeh’s own upbringing and career trajectory, showing how her background shaped her perspective of the people she researched. Prempeh is the founder of the creative studio and consultancy agency A Vibe Called Tech; meeting business mentors is one of the challenges she has faced and continues to experience. Prempeh emphasized that it’s important for her agency to be “rooted in this idea of intersectionality and cultural storytelling,” and she hasn’t met many leaders who have done this while also ensuring their agency is a household name with a long-term history.

Regarding the next generation of makers, Prempeh says we need better support systems, not just one-time accolades or grants. It takes considerable time “to build up a body of work and to feel confident in your work,” and many artists need financial support to create that space. In researching the creators featured in Now You See Me, Prempeh stressed that while short-term help isn’t insignificant, we still need to do more.

“How can we create creative support that allows people that time to develop?” said Prempeh.

“Because my experience is [that] without that structure and support, it’s impossible to keep going. There’ll be some mavericks in between who make it quickly and don’t need that support. Obviously, I love that for them. But I worry about who we miss out on because the structures aren’t in place to let them thrive.”

Left: Grace Jones wearing a black leather jacket and Eiffel Tower hat designed by Patrick Kelly, 1989, © Gilles Decamps. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Janet & Gary Calderwood, & Gilles Decamps, 2014; Center: Outfit from Bianca Saunders’s Spring/Summer 2021collection, “The Ideal Man,” Photo, Silvia Draz; Right: Sketch by LaQuan Smith of a jacket and jumpsuit outfit inspired by the Black Panther film, 2018, © LaQuan Smith

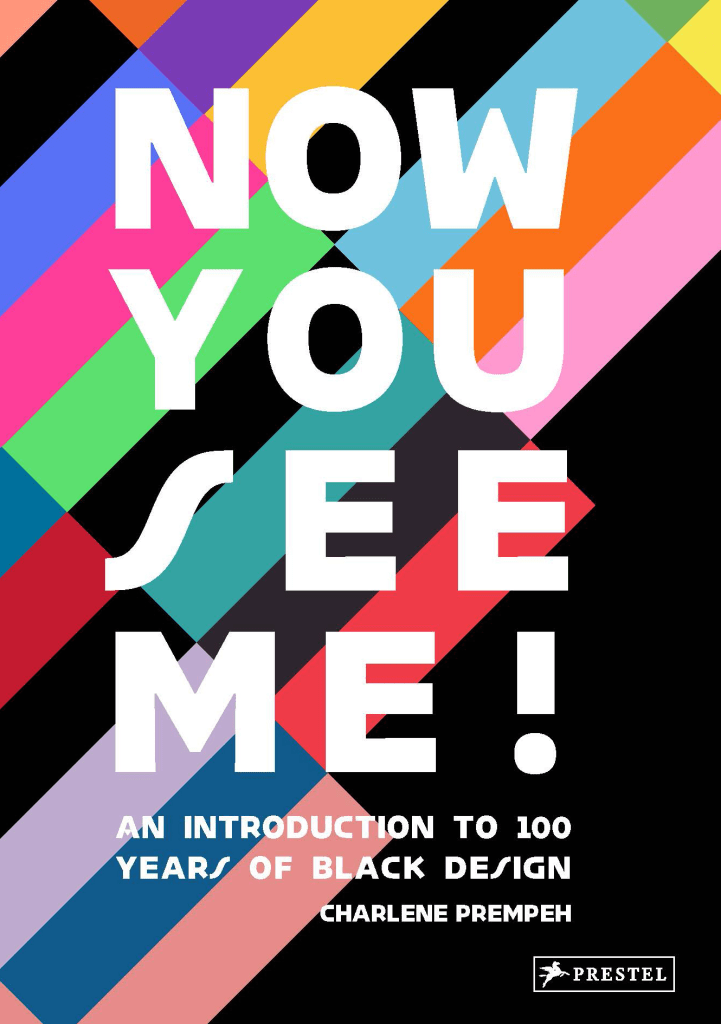

Prempeh worked with graphic design studio Polymode to bring Now You See Me to life. Some of the major visual decisions in the book, explained Prempeh, involved not using photography on the cover or in the section introductions.

We were really clear that we didn’t want to say that any one story or any one image is the most important part of the book. We needed to have some visual language that spoke to all of the different stories.

Charlene Prempeh

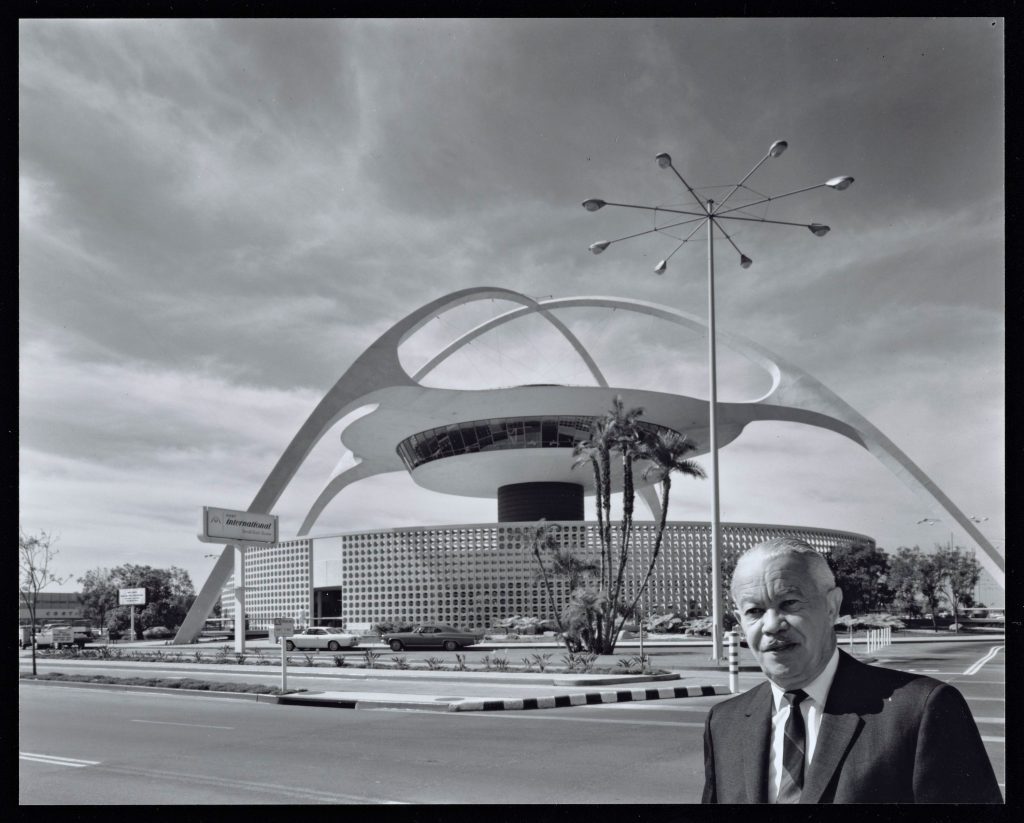

Left: Interior of Gando Primary School, Photo, Siméon Duchoud; Right: Paul R. Williams standing in front of The Theme Building, LAX, 1965, Photo, Julius Shulman © J. Paul Getty Trust, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10).

The book uses a bold typeface: Jaamal Benjamin’s Harlemecc, inspired by the commercial lettering of Harlem Renaissance artist and painter Aaron Douglas. The book’s title, Prempeh explains, plays with the versatility of meanings: “Now you see me” as both a statement and a question that implies these Black creatives have always been important. The fonts VTC Spike, VTC Tre, and The Neu Black—designed by Tre Seals—appear in the subheadlines of the book, while the book copy uses Halyard, designed by Joshua Darden Studios.

“We also really wanted the Blackness of it to come out in the colors,” said Prempeh. Polymode created an overall look that incorporated “African fabric and cloth block colors,” as described on the studio’s website.

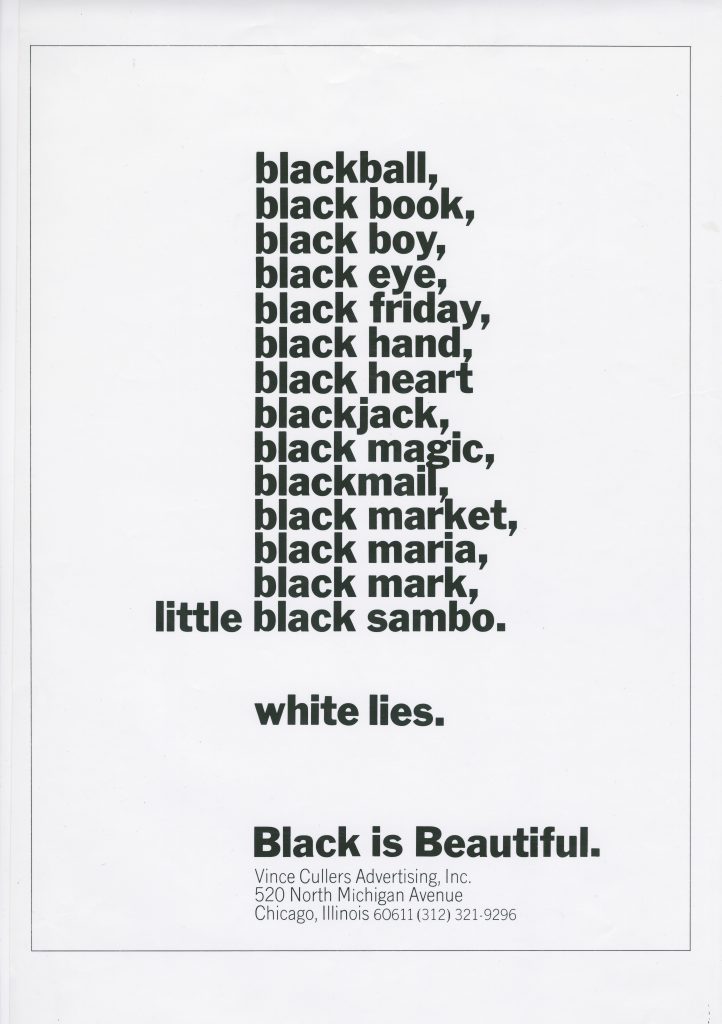

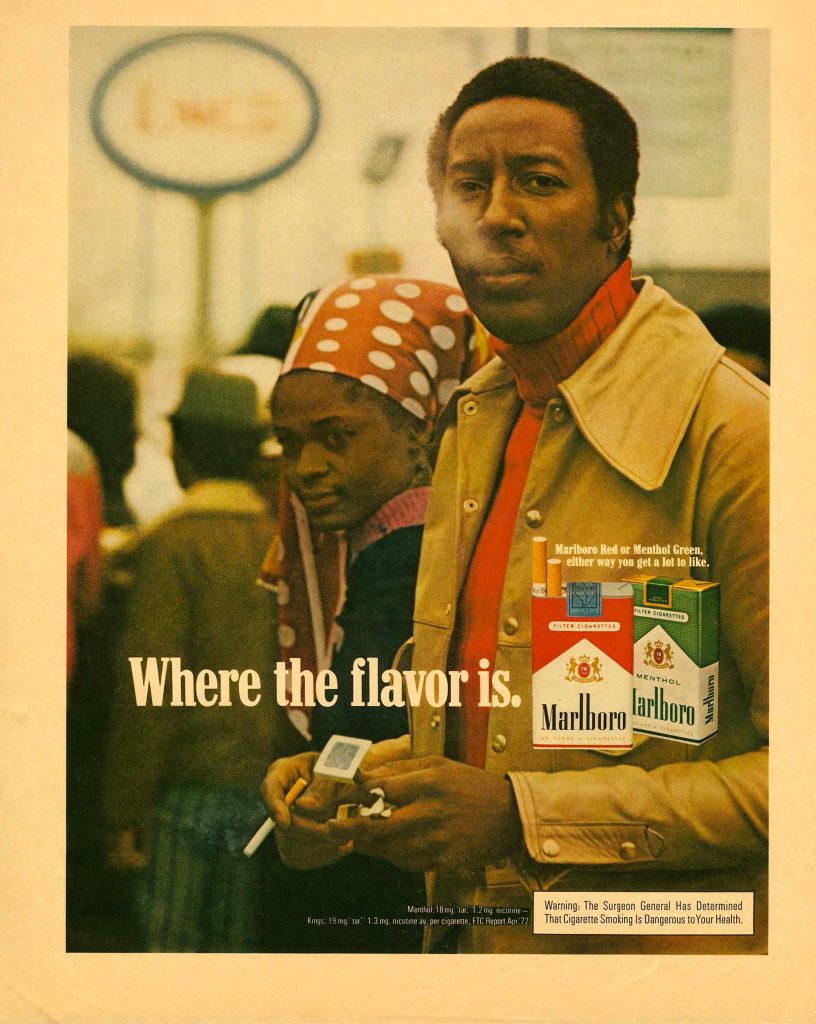

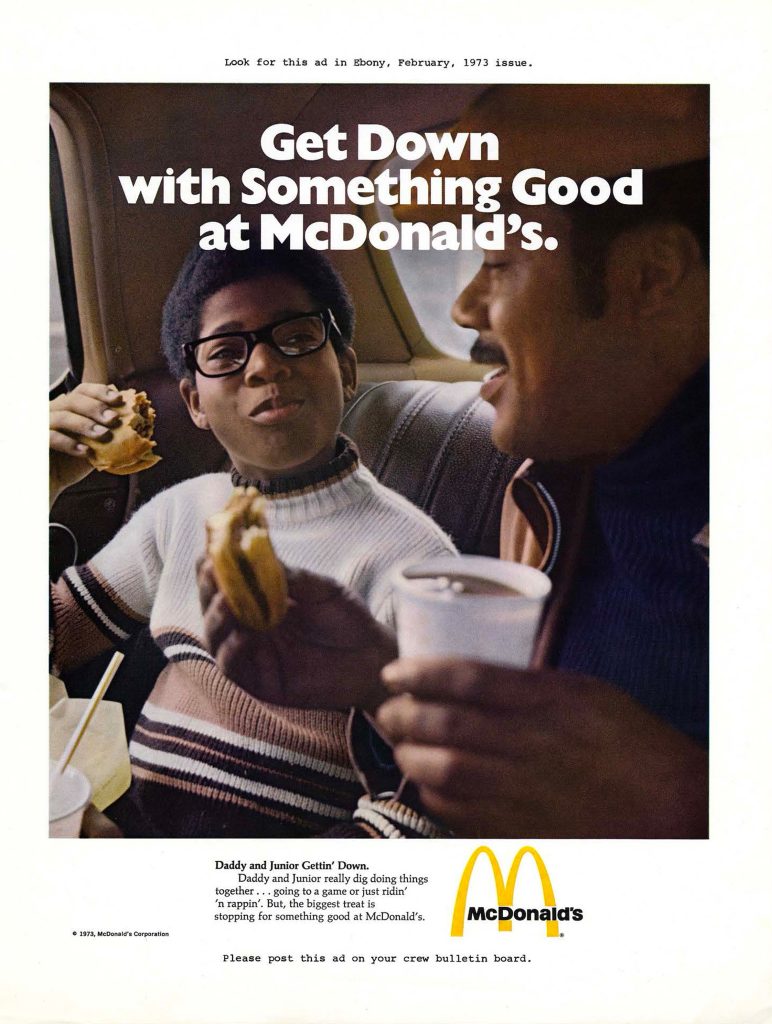

Left: Emmett McBain, 1968. Reproduced with kind permission of Letta McBain. Courtesy of University of Illinois Chicago, Special Collections and University Archives; Center: Emmett McBain, 1972. Reproduced with kind permission of Letta McBain. Courtesy of the Emmett McBain Afro-American Advertising Poster Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution; Emmett McBain 1973. Reproduced with kind permission of Letta McBain. Courtesy of the Emmett McBain Afro-American Advertising Poster Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

While the book contains numerous stories and spans many eras, its design and size make it easy to carry in a bag—a contrast from some larger, coffee-table-style books often published about histories like these.

“As much as the book is beautiful and the pictures are really, really beautiful, we wanted to make sure people took the stories home with them,” said Prempeh.